In our efforts to improve the lives of Restavek girls, we have made a conscious decision to refrain from showing images of their suffering in our media.

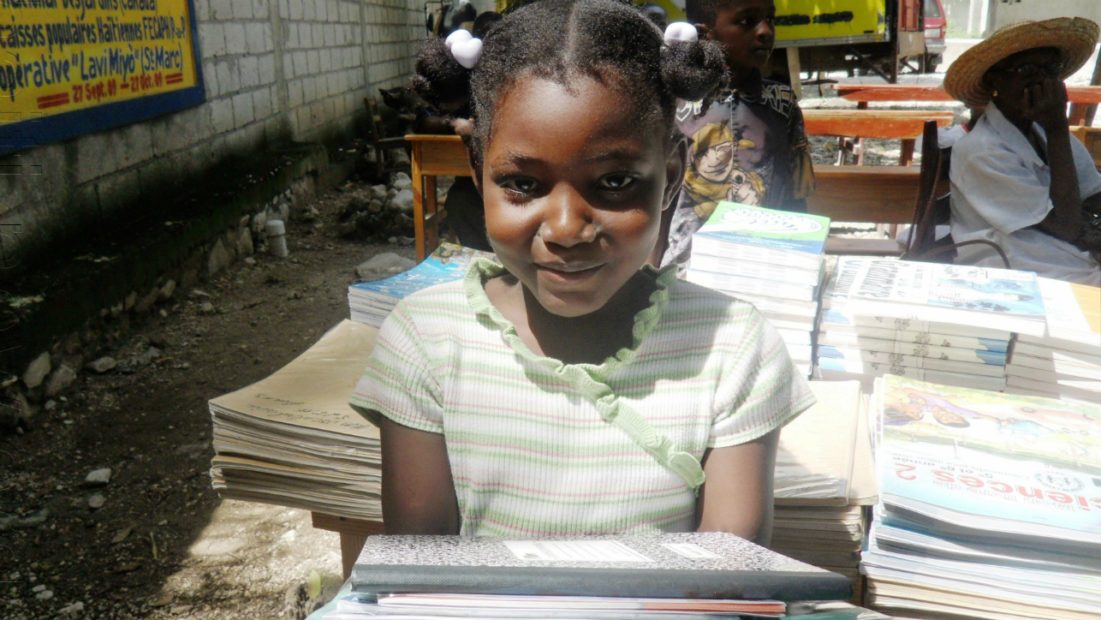

We want to transmit the story of these mostly girl children, sent into domestic servitude by impoverished rural families, to the world. But we feel that using words to describe their plight, along with positive images of the girls themselves, strikes an essential ethical balance between reality, empowerment, dignity and protection.

Their families, due to extreme poverty, send their young daughters to live with marginally better off families in the city. In exchange for household work, the idea is that the girls will get food, shelter and a chance at an education. The reality most find themselves in is a brutal one where they are treated as less than human.

The Reality

Sixty-five percent of Haitian households lack running water (1), so it is largely left to Restavek children to haul heavy buckets of water from a local water source. They are expected to do all of the household chores, from washing clothes and dishes in buckets, to disposing of human waste and cooking food they do not get to eat. They live on scraps, sleep on rags under tables, take care of children they may not play with, may not speak unless spoken to and are whipped with a rigwaz, a whip sold in Haiti for use on Restavek children.

They rarely get the chance to attend school, and if they do, they are looked down upon as Restavek, a derogatory Creole term that literally means “to stay with.” They often can’t afford textbooks or supplies.

Furthermore, as they are largely hidden and marginalized members of society, they are regularly subjected not only to physical but verbal and sexual abuse by the families they serve. Their lives are ones of suffering, without power or voice.

But as important as it is to tell this story to a world that is largely ignorant of it, it is equally important to do such telling in a way that does not further victimize.

Haiti Now’s reasons for the choice to refrain from visually portraying the hardships of Restavek girls’ lives include:

- The desire to empower the girls rather than further victimize them by putting such images out into the online world, potentially forever

- To preserve their dignity and autonomy

- To protect them from reprisals from host families

- To emphasize the hopeful possibilities of their lives

Denis Kennedy, in the Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, writes, “On the television, in the newspaper, in the mail — the public face of the aid industry is never far away. This is a face which is quite literally a face, that of the hungry child, helpless mother, homeless refugee.”(2)

“Through these faces,” he says, “aid agencies sell themselves and their missions; they use marketing techniques honed over the decades.”(3)

It is an endeavor, Kennedy says, that is not without “ethical perils.”(4)

Haiti Now wants to empower, not patronize the people being helped, avoiding adopting what some in humanitarianism refer to as the ‘savior mentality.’ Using imagery that is respectful, that does not indulge in or forever memorialize suffering, is a key component of that. Imagery must be used responsibly.

On one hand, Kennedy says, the modern technology of photography and marketing has bridged vast physical and psychological distances and allowed disparate groups to help one another, hugely expanding what humanitarianism is capable of. On the other, however, the technologies that have enabled such helping have also managed to create what he refers to as the “commodification of suffering.”(5)

This “commodification” is something that Haiti Now’s founder, Alex Lizzappi, wants to avoid. Of the 700+ Restavek girls the organization has helped through the provision of tuition, books and school supplies, Lizzappi says,

“I know each recipient personally, so I am naturally inclined to protect them by looking at the issue from their point of view.”

Of images which portray suffering, he says, “I would not want to be the subject of those photos. The students are aware of the charities using this type of image and generally, the idea of being associated with poverty and suffering leads them to feel shame and discomfort.”

Further, Lizzappi says, “This kind of photo serves exclusively the mindset of ‘donors as saviors,’ and has created misrepresentations and misunderstandings about developing countries. I think the ‘imagery of suffering’ decontextualizes their reality and strips them of agency and voice.”

According to Kennedy, “When victims are stripped of context, … they become personless — they lose their human dignity. The reliance on such images … can discard that which is most human about the victim: autonomy, dignity and context.”(6)

The fundamental goal of Haiti Now is to empower Restavek girls to achieve a lifetime of emotional and economic independence, first through providing tuition, books and school supplies, and now through building a residential school. The bedrock of its value system is empowering Restavek girls; therefore it acts this out through its stance on the use of imagery in its media.

Holding Truth, Preserving Dignity

Haiti Now feels that it is most powerful and appropriate to tell the girls’ stories using words, and that using words strikes the right balance between the importance of relaying facts and respecting dignity. It is essential to get that story out to the world; many people do not know the story of the Restavek girls of Haiti.

Rather than being barraged by images of girls hauling water or washing clothes, images that may be fixed in social media forever, Haiti Now believes that its supporters would rather see the same thing that we want to see: images of happier girls building their futures, healing from the past, learning, growing and beginning to find their voices.

In fact, while studies show that negative imagery does ‘sell’ on average better than positive imagery — that is, showing a suffering child rather than a happy, helped child — they also show that such support comes at a steep cost. People often report that though they may give to such a charity, they often do so with anger and the feeling that they have been manipulated. The same studies show that charities who engage in the use of positive imagery engender similarly positive feelings in the public, and that they report a greater willingness to donate in the future to such causes.(7)

This is the type of relationship which Haiti Now is interested in developing with its supporters, says Lizzappi.

Donors as Partners

“I see donors as partners,” says Lizzappi. “We do not have a marketing tactic for donors, we have communication that wants to be as accurate as possible about our intentions, our objectives, our plans, our success, and our failures. We do not overpromise and we take each word very seriously.”

“The relationship wants to be based on reason and data to enable donors to stand for what they believe in, versus pitching and pulling emotional strings; this type of partner is for the long haul or at least until we deliver the intended outcomes.”

By outcomes, Lizzappi means that the girls who have gone to the residential school Haiti Now is planning to build have measurable and tangible skills; the endeavor of creating these skills is where the organization is looking for partners. He feels that Haiti Now effectively connects recipients and donors in working to overcome extreme poverty and exploitation together. But the driving force is based on the Restavek girls’ needs and their view of the solution.

“Often, among charities, donors and foundations, there is a ‘beggars can’t be choosers’ mentality in the way they operate institutionally. Often the financial strength and influence and growth of the charity or donor foundation is privileged and paramount ahead of recipients’ needs.

“We are operating with the recipients first, with a mindset that they are the owners of the mission, and we are safeguarding the mission for all parties.”

Please consider giving to Haiti Now and helping us raise money to build a residential school for the Restavek girls of Haiti. We believe our supporters join us in holding the girls in the highest esteem and wanting to protect their dignity. This is one of Haiti Now’s most fundamental values.

We also hold our supporters in the highest esteem, and that is why, while we don’t use a lot of imagery depicting suffering, the other bedrock of our value system is transparency. Our website provides full information on where donations go, and always has. We are extremely grateful for whatever support you are able to give.

(1) HHRSI Access to Improved Water. This data was produced by Fafo Research Foundation and the Institut Haitien de l’Enfance.

(2) Denis Kennedy, “Selling the Distant Other: Humanitarianism and Imagery — Ethical Dilemmas of Humanitarian Action,” in The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, Volume 28 (2009), pp. 1 -25

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid 2.

(5) Kennedy, 1

(6) Ibid 2

(7) Arvid Erlandsson, Artur Nilsson & Daniel Västfjäll, “Attitudes and Donation Behavior When Reading Positive and Negative Charity Appeals,” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 30:4, (2018) pp. 444-474

References

Erlandsson, Arvid, Artur Nilsson and Daniel Västfjäll. “Attitudes and Donation Behavior When Reading Positive and Negative Charity Appeals.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 30:4, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2018.1452828.

HHRSI Access to Improved Water. Data was produced by Fafo Research Foundation and the Institut Haitien de l’Enfance. (2020). https://public.tableau.com/profile/haiti.now#!/vizhome/HHRSI_AccesstoImprovedWater/FAFOTemplate.

Kennedy, Denis. “Selling the Distant Other: Humanitarianism and Imagery — Ethical Dilemmas of Humanitarian Action.” Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, Volume 28, (2009). https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/411.