The entire Haiti Under President Martelly Current-122015. Below, I have listed extrapolated parts that interested me.

Political conflict embroiled Aristide and the opposition, however, and led to the collapse of his government in 2004, and Aristide again went into exile, (? forced by the US ?) eventually ending up in South Africa.

Some 17% of the country’s civil service employees were killed, and the presidential palace, the parliament building, and 28 of 29 ministry buildings were destroyed. Along with the buildings, government records were destroyed; reestablishing and expanding transparency in government spending has been particularly challenging.

Additional concern has been raised over the Martelly Administration’s decision to replace most of the 120 mayors elected in 2006, whose terms have expired, with government appointees.

The new CEP finally set about scheduling elections for 2015. They faced a difficult process:

electoral council personnel were largely inexperienced in elections work, and internal procedures had to be established. The races would also be complex: the CEP deemed 166 political parties and

platforms qualified to participate and 1,857 candidates qualified to run for the 20 Senate seats and 118 Chamber of Deputies seats (the latter was recently expanded from 99 seats). Among the

Senate candidates is Guy Philippe, leader of the 2004 coup overthrowing President Jean-Bertrand Aristide; Philippe is wanted in the United States under sealed indictment. About 70 candidates

registered to run for president.

The CEP did not clear former Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe and six other former government ministers to run for president and did not list its reasons. According to Haitian law, the Senate must certify that candidates have not misused government funds before they can run for office. None of the rejected candidates had received the required “discharge.” Lamothe said he requested a discharge but that Parliament was dissolved before it could issue one. He said that on May 20, 2015, a judge issued a ruling confirming that, without a functioning parliament, it is impossible to comply with the discharge requirement and that it should therefore be waived, and that his exclusion was politically motivated.12 According to another report, the superior court of auditors and administrative disputes alleged that irregularities had taken place under Lamothe’s role as minister of planning (a post he held simultaneously with being prime minister); Lamothe contested the findings.

First Lady Sophia Martelly was rejected as a Senate candidate, apparently on the basis of dual citizenship and for failing to get a discharge. Although she was not elected, she had handled public funds through a government program. President Martelly said that if his wife’s rejection was politically motivated, it could discredit the process. Others saw the action as a sign of the CEP’s independence.

Haiti began to ease its long-term political crisis by holding the first round of legislative elections on August 9, 2015. Polling in some areas was marred by delays, disorder, low turnout—only 18% of voters cast ballots—and sporadic violence. Organization of American States (OAS) electoral observers found that such irregularities were not sufficient to invalidate the results as a whole. nonetheless, violence and technical irregularities were severe enough that the CEP invalidated the vote in 13% of polling centers; these races were re-held in the ensuing October elections. Local observer organizations said the problems were more widespread, reporting fraud, irregularities, and violence in half of all voting centers. For the first time, according to the head of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), Sandra Honoré, Haiti had penalized instigators of electoral violence. Electoral officials disqualified 14 candidates for engaging in or inciting violence during the elections.

Despite those issues, the CEP managed runoff legislative elections for 18 of the 20 Senate seats and most of the 119 Chamber of Deputies seats and first-round presidential elections simultaneously with elections for 1,280 municipal administrations on October 25.

The CEP declared that Jovenel Moise, the candidate for Martelly’s party (the Haitian Bald Head party, PHTK) and a political novice, and Jude Celestin, who lost to Martelly in 2011, would

proceed to a runoff. Moise, a relatively unknown agricultural businessman who campaigned as “The Banana Man,” garnered almost 33% of the vote, to Celestin’s 25%. Celestin was the

government’s construction chief under the Préval administration. He was the government-backed candidate in the last presidential elections, and his campaign faced charges of fraud in those

elections.

A local observation group published a report with long lists of irregularities, saying that there was a “vast operation of electoral fraud.” 17 The report stated that the majority of political parties were “clearly involved in the commission of violence and electoral fraud,” and that the governing party was one of the most aggressive. It also said the CEP lacked transparency in its tabulation.

Still others acknowledge that irregularities occurred, but say that the opposition has failed to present evidence that they constitute orchestrated fraud, and instead continue to demand remedies

outside established procedures for electoral dispute resolution.

According to the constitution, the newly-elected legislators are to take office on January 11 and the new president on February 7, 2016. Elections for 1,280 local administrations were to be held simultaneously with the presidential runoff elections. About 38,000 candidates are participating in those races. Those are single-round political contests; a simple majority suffices to win. Now it is unclear whether the local races will still be held with the presidential runoff elections, whenever they take place, or be held separately. This would simplify the process but incur additional costs

During most of Martelly’s first year in office, Haiti was without a prime minister, which severely limited the government’s ability to act and the international community’s ability to move forward with reconstruction efforts. Martelly was not able to form a government for almost five months because of disputes with a parliament dominated by the opposition Inité coalition over his first two nominees for prime minister. Dr. Garry Conille, a senior U.N. development specialist and former aide to then-U.N. Special Envoy to Haiti Bill Clinton, was confirmed as prime minister on October 4, 2011. Conille lasted only four months in the position, after which he was reportedly pressured by President Martelly to resign in part because of disagreements over an investigation

of $300 million-$500 million in post-earthquake contracts linked to Martelly and former Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive. Bellerive, now an adviser to Martelly, and also his cousin, said he was the victim of a smear campaign.

Authorities in the Dominican Republic are also investigating corruption allegations linked to President Martelly. According to Dominican journalist Nuria Piera, a company owned by Dominican Senator Felix Bautista was awarded a $350 million contract for reconstruction work in Haiti, despite not meeting Haitian procurement requirements. Bautista allegedly gave over $2.5 million to President Martelly before and after he won the election.

After the first prime minister resigned, another three months went by before a new prime minister was confirmed. Laurent Lamothe, Martelly’s foreign affairs minister and a former telecommunications executive, was named prime minister in May 2012. Parliament approved his cabinet and government plan soon thereafter. The cabinet included two new posts: one minister to address poverty and another to support farmers.

Because Martelly and much of his team—reportedly mostly childhood friends—lack political or management experience, many observers are concerned about the president’s ability to carry out his promises of free and compulsory education, job creation, agricultural development, and strengthened rule of law. That political inexperience may have contributed to the gridlock and

animosity between Martelly’s administration and the parliament that have characterized Haitian politics since he took office. His justice minister resigned after police violated the immunity

legislators have and arrested a legislator who had allegedly escaped from jail.

President Martelly named three members to the Supreme Court, including its president. The latter post had been vacant for six years. According to the State Department, this is the first time in over 25 years that Haiti has those three branches of government in place.

The U.N. human rights expert also voiced concern over the politicization of the judiciary and the national police under the Martelly Administration, stating that “the practice of appointing or

removing judges to advance partisan or political ends … continues unabated.” U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon echoed that concern, adding that institutional politicization and frequent

Cabinet changes hindered the efforts of MINUSTAH and other international donors to build capacity within those institutions.31 Human rights expert Forst also criticized the Martelly

Administration for making arbitrary and illegal arrests and for threatening journalists.

“They have a work force of 4.2 million people and in formal jobs they have only 200,000,” said Mariano Fernandez, adding that “this is a permanent source of instability.”

Some observers are concerned that, without the checks and balances of a legislature, corruption may expand unchecked. There have been investigations into corruption involving President

Martelly, some of his advisers, and family members—including his wife, Sophia Martelly—along with reports that prosecutors who objected to interference from the executive branch in these

cases were fired or fled the country.34 In April 2015 Woodly Etheart, an indicted head of a kidnapping ring with close ties to the president’s family, was freed from prison. Etheart’s trial

lasted about two hours and was run by a judge who has previously been accused of bowing to the executive branch’s wishes. Human rights activists and other critics say the hasty decision was a

setback in the fight against organized crime.

MINUSTAH’s mandate includes three basic components: (1) to help create a secure and stable environment; (2) to support the political process by fostering effective democratic governance

and institutional development, supporting government efforts to promote national dialogue and reconciliation and to organize elections; and (3) to support government and nongovernmental

efforts to promote and protect human rights, as well as to monitor and report on the human rights situation.

MINUSTAH’s current authorization runs through October 15, 2015. The mission’s budget for this year (July 1, 2014-June 30, 2015) is about $500 million. The U.N. has been gradually reducing MINUSTAH’s number of troops since 2012. In October 2014 the Security Council passed a resolution that will reduce military personnel by more than half, to a maximum of 2,370 military personnel.

The European Union stated that demonstrations with a socioeconomic angle had increased by 30%, and that “there continue to be grave social and economic inequalities that represent a real threat to Haiti’s stability and security.” The Group of Friends stated that: security, respect for human rights and the rule of law, and development are interdependent and reinforce stability. We therefore underscore the importance of systematically addressing the issues of unemployment, education and the delivery of basic social services, and of ensuring the economic and political empowerment of women.

MINUSTAH and the U.N. have been widely criticized for not responding strongly enough to an outbreak of cholera in October 2010, the first such outbreak in at least a century in Haiti. A team of researchers from France and Haiti conducted an investigation at the request of the Haitian government. They reported that their findings “strongly suggest that contamination of the Artibonite [River in Haiti] and 1[sic] of its tributaries downstream from a [MINUSTAH] military camp triggered the epidemic,” noting that there was “an exact correlation in time and places between the arrival of a Nepalese battalion from an area experiencing a cholera outbreak and the appearance of the first cases in [the nearby town of] Meille a few days after.” Other studies have come to the same conclusion. While the authors of the study caution that the findings are not definitive, they and others have suggested that “to avoid actual contamination or suspicion happening again, it will be important to rigorously ensure that the sewage of military camps is handled properly.”

The U.N. has been under increasing pressure to take full responsibility for introduction of the disease. Over 5,000 cholera victims or relatives of victims have filed legal claims against the U.N., demanding reparations, a public apology, and a nationwide response including “medical treatment for current and future victims, and clean water and sanitation infrastructure.”

U.N. announced in early 2013, however, that it would not compensate cholera victims, claiming diplomatic immunity. The Boston-based Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti filed a class action suit against the U.N. on behalf of victims in a U.S. federal court in October 2013, seeking establishment by the U.N. of a standing claims commission to address claims for harm, and compensation for victims, including remediation of Haiti’s waterways, provision of adequate sanitation, and “$2.2 billion that the Haitian government requires to eradicate cholera.” In January 2015, a U.S. federal judge dismissed that class action suit, determining the U.N. to be immune because of treaties. Two other lawsuits by cholera victims are still pending in U.S. courts.

Charges of sexual abuse by MINUSTAH personnel have also fueled anti-MINUSTAH sentiment. The U.N. has a zero-tolerance policy toward sexual abuse and exploitation.45 In the case of peacekeepers, the U.N. is responsible for investigating charges against police personnel, but the sending country is responsible for investigating charges against its military personnel. The U.N. returns alleged perpetrators to their home country for punishment. Five MINUSTAH peacekeepers from Uruguay were sent home in 2011, to be tried on charges of sexually abusing an 18-year-old man at a U.N. base while filming it on a cellphone. According to the U.N., among 11 substantiated cases in 2012 were at least two cases of sexual exploitation of children by U.N. police. The investigations led to three members of a Pakistani police unit being convicted of raping a 14-year-old boy in one of the cases. The trial took place in March 2012 in Haiti but was conducted by a Pakistani military tribunal, which dismissed the men from the military and sentenced them to one year in prison. The unit had five cases pending as of June 1, 2015.

A major U.N. review of peacekeeping missions recommended that countries that disregard children’s rights in armed conflict should be barred from U.N. peacekeeping missions; that disciplinary action, or lack thereof, against sexual exploitation and abuse by U.N. personnel should be made public; and that investigations should be required to be completed in six months, rather than the average 16 months it currently takes.

Haiti’s poverty is massive and deep. There is extreme economic disparity between a small privileged class and the majority of the population. Over half the population (54%) of 10 million people lives in extreme poverty, living on less than $1 a day; about 80% live on $2 or less a day, according to the World Bank. Poverty among the rural population is even more widespread: 69% of rural dwellers live on less than $1 a day, and 86% live on less than $2 a day. Hunger is also widespread: 81% of the national population and 87% of the rural population do not get the minimum daily ration of food defined by the World Health Organization. In remote parts of Haiti, children have been dying of malnutrition. Food security worsened throughout Haiti following Hurricanes Isaac and Sandy in 2012, which destroyed about 70% of Haiti’s crops. Some 1.5 million people live in severe food insecurity in rural areas affected by the storms. As many as 450,000 people were at risk of severe acute malnutrition, including at least 4,000 children less than five years of age.

The global economic crisis led to a drop of about 10% in remittances from Haitians abroad, which amounted to about $1.65 billion in 2008, more than a fourth of Haiti’s annual income. Damage and losses caused by the 2010 earthquake were estimated to be $7.8 billion, an amount greater than Haiti’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2009. 54 Haiti’s GDP contracted by slightly more than 5% in 2010, but grew by 5.6% in 2011. Growth fell again, to 2.8% in 2012, slowed by hurricanes, drought, and “delays in implementing key public investment projects.” According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Haiti’s GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate was 4.3% in 2013; estimated at 2.7% in 2014, dropping slightly due to the effect of drought on the agricultural sector and the underperformance of government projects; and expected to rise to 4.2 % by 2016.

The likelihood that economic growth will contribute to the reduction of poverty in Haiti is further reduced by its enormous income distribution gap. Haiti has the second-largest income disparity in the world. Over 68% of the total national income accrues to the wealthiest 20% of the population, while less than 1.5% of Haiti’s national income is accumulated by the poorest 20% of the population. When the level of inequality is as high as Haiti’s, according to the World Bank, the capacity of economic growth to reduce poverty “approaches zero.”

In 2009, Haiti passed a minimum wage law. The law mandated increases in wages in two phases. In 2010, the minimum wage rose from about $1.75 per day to $3.75 per day, and in October 2012, it increased to $5.00 per day. The average daily wage for textile assembly workers is $5.25, above the new minimum wage, so some manufacturers said that they would have to raise wages

proportionally. Despite the wage increase, the fundamental inequality of Haitian society remains basically unchanged.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Haiti had the highest number of cholera cases in the world. The Haitian government has recorded about 712,330 cases, with many cases believed to go unreported. Over 8,600 people have died because of cholera.60 The number of new cases has decreased over time but spikes during the rainy season, when flooding spreads the disease. Haiti continues to have the largest cholera epidemic in the Western Hemisphere.

President Martelly authorized a cholera vaccination program that began in April 2012. (The previous government declined a pilot vaccination program, arguing that vaccinating only a

portion of the population would incite tensions among those not vaccinated.) The pilot program inoculated only about 1% of the population: 90,000-100,000 people in some of the poorest areas

of Port-au-Prince and in the rural Artibonite River Valley. Partners in Health (PIH), a Boston based nongovernmental organization, which has worked in Haiti for decades, and its Haitian

partner in the pilot program, GHESKIO, say the program’s success led the Haitian Ministry of Health to conduct targeted immunization campaigns in other parts of the country. About 300,000

more vaccinations were planned for late 2014. The vaccination is 60% to 85% effective and costs $3.70 per patient for the two-dose treatment. “[T]here is zero funding available” for the Haitian government’s $3 million plan to vaccinate 300,000 people in 2015, however, according to Senior U.N. Coordinator for the Cholera Response in Haiti Pedro Medrano. Other, immediate, small-scale preventive measures include building latrines and distributing soap, bleach, and water-purification tablets. Treatment includes oral rehydration salts, antibiotics, and IV fluids. The United States has spent over $95 million for such preventive measures, and supporting staff and supplies for 45 cholera treatment centers and 117 oral rehydration posts, and working with the Haitian Ministry of Health to set up a national system for tracking the disease. But most observers say cholera will persist in Haiti until nationwide water and sanitation systems are developed. This would cost approximately $800 million to $1.1 billion, according to the New York Times.

Haiti’s first wastewater treatment site was opened in the fall of 2011. A study released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that the strain of cholera in Haiti is changing as survivors develop some immunity to the original strain. This could be an indication that the disease is becoming endemic in Haiti.

In 2012 the U.N. announced an effort to raise over $2 billion for a 10-year cholera eradication plan, to which it will contribute $23 million, or about 1% of what it says is needed. Of the total amount, about $450 million was needed for the first two years (February 2013-February 2015); only 40% of that had been “mobilized” as of November 2014. Of the $72 million needed for

2014-2015, donors have contributed only $40 million.68 In late 2014, the senior U.N. coordinator for the cholera response in Haiti warned that, at the current “disappointing” rate of funding, “it

would take more than 40 years to get the funds needed for Haitians to gain the same access as its regional neighbors to basic health, water and sanitations systems.”69 Medrano suggested that with better funding cholera could be eliminated from Haiti in about a decade. “Like Ebola,” he said, “cholera feeds on weak public health systems, and requires a sustained response.… The donor

community has to do better.”

The U.N. secretary-general also had commissioned a report, which recommended a strategy to move Haiti beyond recovery to economic security. Although published in 2009, many of its

findings still apply to a post-earthquake Haiti. According to the U.N. report, “the opportunities for [economic development in] Haiti are far more favorable than those of the ‘fragile states’ with

which it is habitually grouped.” The report’s author, economist Paul Collier, is known for his book, The Bottom Billion, which explores why there is poverty and how it can be reduced.

Among his reasons for optimism regarding Haiti: Haiti is part of a peaceful and prosperous region, not a conflictive one; and while political divisions and limited capacity make governing difficult, Collier believed that Haiti’s leadership at the time was “good by the standards of most post-conflict situations … [exhibiting] integrity, experience and ability, and a deep concern with

the maintenance of social peace.” The U.N. report recommended that modest and focused actions be taken to build economic security on the foundation of social stability that has been built in

Haiti in recent years. Because that stability was—and remains—fragile, the report advised that such actions should be taken immediately and should focus on strengthening security by creating

jobs, especially in the garment and agricultural sectors; providing basic services; enhancing food security; and fostering environmental sustainability. These strategies remain part of the post-earthquake approach to development.

Collier and other analysts note that Haiti has an important resource in the 1.5 million Haitians living abroad, for their remittances sent back home, technical skills, and political lobbying. The efforts of Haitian Americans and others lobbying on Haiti’s behalf led to another advantage Haiti has: the most advantageous access to the U.S. market for apparel of any country, through the

HOPE II Act (the Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through Partnership Encouragement Act, P.L. 110-246; see “Trade Preferences for Haiti” section below). Supporters say the HOPE Act

provides jobs and stimulates the Haitian economy. Critics worry that it exploits Haitians as a source of cheap labor for foreign manufacturers, and hurts the agricultural economy by drawing

more people away from farming.

U.S. and Canadian companies have conducted exploratory drilling in Haiti, reporting a potential $20 billion worth of gold, copper, and silver below Haiti’s northeastern mountains. While discoveries of such mineral wealth have led to economic booms in many countries, they also bring risks such as environmental contamination, health problems, and displacement of communities. And like many poor countries that could use the revenue from mineral extraction, Haiti does not have the government infrastructure to enforce laws that would regulate mining— reportedly, the last time gold was mined there was in the 1500s. The Préval government negotiated the agreement with the only company that has full concessions; the terms of that agreement would return to Haiti $1 out of every $2 of profits, a high return. Prime Minister Lamothe said the government is already drafting mining legislation to establish royalties paid to the government and safeguards for citizens and the environment in mining areas.

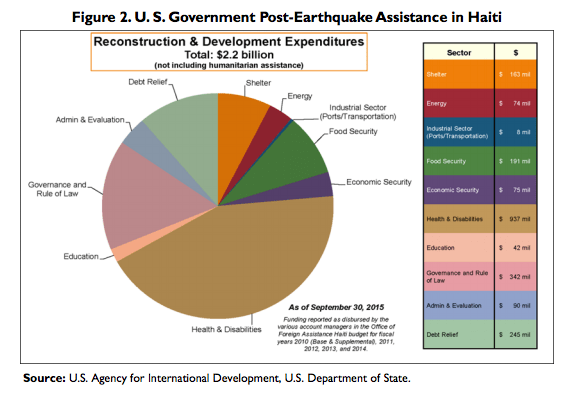

U.S. assistance to Haiti focuses on the four key sectors outlined in the Action Plan for Reconstruction and National Development of Haiti, with funding directed toward infrastructure and energy projects, governance and rule-of-law programs, programs for health and other basic services, and food and economic security programs. Many of the latter type of programs are carried out under the President’s Feed the Future initiative, which aims to implement a country led comprehensive food security strategy to reduce hunger and increase farmers’ incomes. The Administration’s approach is detailed in its “Post-Earthquake USG Haiti Strategy toward Renewal and Economic Opportunity.”

The FY 2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-113) prohibits assistance to the central Haitian government unless the Secretary of State certifies and reports to the Committees on Appropriations that the Haitian government “is taking effective steps” to hold free and fair parliamentary elections and seat a new parliament; strengthen the rule of law in Haiti, including

by selecting judges in a transparent manner; respect judicial independence; improve governance by implementing reforms to increase transparency and accountability; combat corruption,

including by implementing the anti-corruption law enacted in 2014 and prosecuting corrupt officials; and increase government revenues, including by implementing tax reforms, and increase

expenditures on public services.

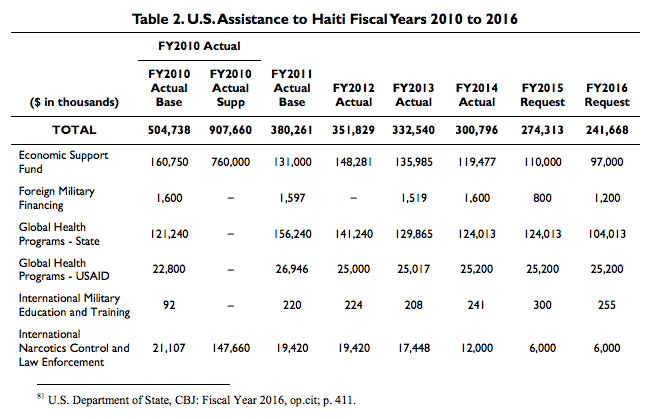

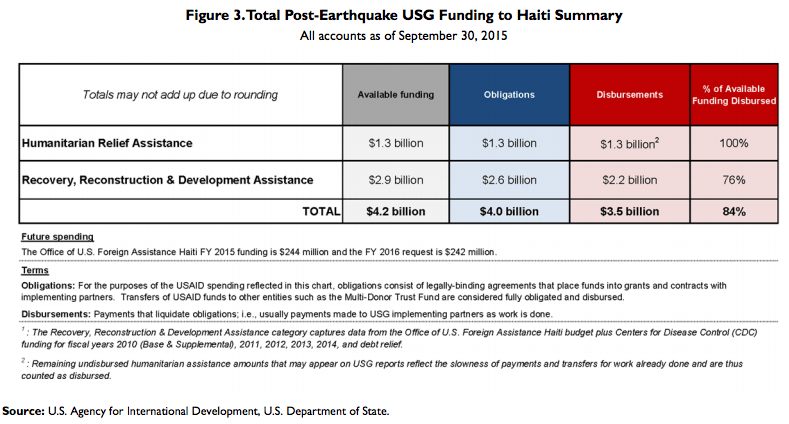

In the aftermath of the earthquake, Congress appropriated $2.9 billion for aid to Haiti in the 2010 supplemental appropriations bill (P.L. 111-212).85 This included $1.6 billion for relief efforts, $1.1 billion for reconstruction, and $147 million for diplomatic operations. Since then, Congress has expressed concern about the pace and effectiveness of U.S. aid to Haiti. According to the U.N. Special Envoy for Haiti’s office, of the approximately $1.2 billion the United States pledged at the 2010 donors conference for aid to Haiti, 19% had been disbursed as of March 2012, and about 33% as of December 2012. All donors had pledged about $6.4 billion, disbursed just over 45% of that as of March 2012, and disbursed 56% of it by the end of 2012.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued several reports on USAID funding for post-earthquake reconstruction in Haiti. In a 2013 report, GAO concluded that “the majority of supplemental funding ha[d] not been obligated and disbursed” as of March 31, 2013.87 The report said that USAID had obligated 45% and disbursed 31% of the $651 million allocated in the FY2010 Supplemental Appropriations Act for bilateral earthquake reconstruction activities. These figures refer only to Economic Support Funds (ESF) provided in the FY2010 supplemental. The supplemental required the State Department to submit five reports to Congress. GAO criticized the State Department for “incomplete and not timely” reports, noting that only four reports were submitted and that they lacked some of the information specifically requested by the Senate Committee on Appropriations, such as a description, by goal and objective, and an assessment of the progress of U.S. programs. The State Department countered that it provides information to Congress through other means as well, such as in-person briefings, according to GAO.

In June 2015 GAO released its latest report, Haiti Reconstruction: USAID Has Achieved Mixed Results and Should Enhance Sustainability Planning. GAO reported that the USAID Mission in Haiti reduced planned outcomes for five of six key infrastructure activities and 3 of 17 key non-infrastructure activities. USAID met or exceeded the target for half of all performance indicators

for key non-infrastructure activities. Mission officials said that inadequate staffing and unrealistic initial plans affected results and caused delays. The mission has therefore increased staffing and

extended its reconstruction time frame for another three years, to 2018. GAO concluded that although the mission in Haiti took steps to ensure the sustainability of its reconstruction efforts,

sustainability planning could be improved at both the mission- and agency-wide levels.

Looking at the broader range of funding available for Haiti, USAID and the State Department report that 100% of the $1.3 billion allotted for humanitarian relief assistance, and 71% of the

$2.3 billion allotted for recovery, reconstruction, and development assistance had been distributed as of March 31, 2015. The recovery, reconstruction, and development assistance includes the

amount pledged at the U.N. recovery conference (and appropriated through the FY2010 supplemental appropriations bill), plus other appropriated fiscal year funds (base FY2010, and

FY2011-FY2014). (It does not include USAID prior year funds reallocated to meet urgent Haitian recovery and reconstruction needs.) Using these figures, the Administration calculates that it has

disbursed 80% of funding available for Haiti.

While Haiti is making some progress in its overall recovery effort, enormous challenges remain. International donors responded to the earthquake with a massive humanitarian effort. Most of the

rubble created by the earthquake has been removed and three-fourths of those living in tent shelters have left the camps. Nevertheless, many criticize the pace and methods of the recovery

process regarding displaced persons. About 61,000 of those who left the camps were forcibly evicted, and about 78,000 live on private land under threat of eviction, with the U.N. expressing concern about the human rights violations involved in such expulsions. Various 2014 estimates on the number of people still living in tent shelters range from 147,000 to 280,000. The latter figure is from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which estimates there are another 200,000 people living with host families or in internal settlements, for a total of 480,000 internally displaced persons.

A major element of U.S. aid to Haiti has been the development of the Caracol Industrial Park in Haiti’s northern region. Although the region was not hit by the earthquake, the project is part of an effort—begun before the earthquake—to “decentralize” development, stimulating the economy and creating jobs outside of overcrowded Port-au-Prince. The Obama Administration said the Caracol park was supposed to create 20,000 permanent jobs initially, with the potential for up to 65,000 jobs; as of October 2012 then-Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said about 1,000 Haitians were employed there.90 As of April 2015 there were 6,200 jobs at the park.

The Caracol Industrial Park has generated much controversy. According to the New York Times, State Department officials acknowledged that they did not conduct a full inquiry into allegations of labor and criminal law violations by Sae-A in Guatemala before choosing the company to anchor the park. Environmentalists, who had marked Caracol Bay to become Haiti’s first marine protected area, were reportedly “shocked” to learn an industrial park would be built next to it. U.S. consultants who helped pick the site said they had not conducted an environmental analysis before recommending the site, the Times reported, and in a follow-up study said the site posed a high environmental risk and that, even if wastewater were treated the bay would be endangered, and the U.S.-financed power plant would have “a ‘strongly negative’ impact on air quality.” Civil society groups argue that the park, built on some of Haiti’s rare arable land, displaced farmers and promotes manufacturing at the expense of agriculture. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported mixed results for U.S. funding at Caracol, which includes $170 million for a power plant and port to support the Industrial Park.

USAID completed the first phase of the power plant with less funding than allocated, and in time to supply the park’s first tenant with power. GAO reports that the Caracol Industrial Park, the

power plant, and the port are interdependent, that “each must be completed and remain viable for the others to succeed.” Yet port construction is at least two years behind schedule, and USAID funding will be insufficient to pay for most of the projected costs, leaving a cost gap of $117 million to $189 million. GAO said it was unclear whether the government of Haiti could find a private company willing to fund the rest of the port costs. Two recent reports criticized labor practices in Haitian factories, including at the U.S.-funded Caracol Industrial Park, alleging widespread underpayment of workers and unsafe working conditions at many of them.

As part of its concern about the effectiveness of U.S. aid to Haiti, Congress has supported efforts over the years to improve the transparency and accountability of the Haitian government’s

spending. Congress prohibited certain aid to the central government of any country that does not meet minimum standards of fiscal transparency through the foreign assistance appropriations act for 2012 (P.L. 112-74). While acknowledging Haiti’s progress toward fiscal transparency, the State Department reported that Haiti did not meet those minimum standards, but waived the restriction on the basis of national interest. In its memorandum of justification, the department argued that, “Without assistance and support, Haiti could become a haven for criminal

activities…. Without sufficient job creation, Haiti could become a greater source of refugee flows….”

According to the U.S. Department of State’s Human Rights report from 2013:

The most serious impediments to human rights involved weak democratic governance in the country; the near absence of the rule of law, exacerbated by a judicial system vulnerable to political influence, and chronic, severe corruption in all branches of government. Basic human rights problems included some arbitrary and unlawful killings by government officials; excessive use of force against suspects and protesters; overcrowding and poor sanitation in prisons; prolonged pretrial detention; an inefficient, unreliable, and inconsistent judiciary subject to significant outside and personal influence; rape, other violence, and societal discrimination against women; child abuse; social marginalization of minority communities; and human trafficking. Allegations continued of sexual exploitation and abuse by members of … MINUSTAH. Violence and crime within camps for approximately 369,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) remained a problem. In addition there were multiple incidents of mob violence and vigilante retribution against both government security forces and ordinary citizens, including setting houses on fire, burning police stations, throwing rocks, beheadings, and lynchings.

The U.N. Independent Expert on the Situation of Human Rights in Haiti, Michel Forst, made a blunt assessment of the current state of human rights in Haiti in his final address before the U.N.’s Human Rights Council. Before stepping down from the position he said, “I cannot, and I do not want to hide from you my anxiety and disappointment regarding developments in the fields of the rule of law and human rights….” Saying that “impunity reigns,” the human rights expert said, “It is inconceivable that, under the rule of law, those responsible for enforcing the law feel

authorized not to respect the law and that such behavior goes unanswered by the judicial system.” Forst strongly criticized the nomination of magistrates for political ends, citing the case in which he said the current Minister of Justice appointed a judge especially for the purpose of ordering the release of Calixte Valentin, a presidential adviser being held in preventive detention on a murder charge. His statement bemoaned threats against journalists, arbitrary and illegal arrests, and the failure to implement identified solutions that would improve conditions in the Haitian prison system—which he said “remains a cruel, inhuman and degrading place.” He expressed his wish that the Martelly Administration take up the work of the Ministry of Justice under President Préval in the revision of the penal code. Forst applauded the strong efforts of the Préval and Martelly Administrations in strengthening the police, with international support, and the renewed public confidence in the police. He noted persisting problems however, commenting that the case of a person tortured to death in a police station in a Port-au-Prince suburb was not an isolated incident.

The human rights specialist also noted positive developments in human rights, including the role played by the Office of Citizen Protection, Haiti’s human rights ombudsman, in promoting

respect for human rights, and a strong civil society with professional human rights organizations advocating for issues such as women’s rights and food security. Forst also praised the

appointment of a Minister for Human Rights and the Fight against Extreme Poverty. An aide to the Prime Minister, George Henry Honorat, was killed March 23, 2013, in a drive-by

shooting. Motives are not known, but Honorat was also the editor in chief for a weekly newspaper, Haiti Progres, and was secretary general of the Popular National Party that opposed

the Duvalier regimes.

Concerns over Haitians and People of Haitian Descent in the Dominican Republic

A September 2013 court ruling in the Dominican Republic caused enormous controversy because it could deny citizenship to some 200,000 Dominican-born people, mostly of Haitian descent, making them stateless. The Dominican Republic’s 1929 constitution adhered to the principle that citizenship was determined by place of birth. The country’s 2010 constitution excluded from citizenship “those born to … foreigners who are in transit or reside illegally in Dominican territory.” For decades, Haitians have been brought into the Dominican Republic to work in sugar fields and, more recently, construction. The Dominican Constitutional Court ruled that the 2010 definition must be applied retroactively. It also reinterpreted the provision in the 1929 constitution which excluded from citizenship children born to foreigners “in transit,” so that it excluded all those born to undocumented foreigners. (Previously, the “in transit” clause had mostly been applied to members of the diplomatic corps or others in the country for a limited, defined period.) The decision stripped a 29-year old Dominican-born woman of Haitian descent of her citizenship, and denied citizenship to her Dominican-born children. The court also ordered Dominican authorities to conduct an audit of birth records to identify similar cases of people formally registered as Dominicans since 1929, saying they would no longer qualify for citizenship under the new constitution. The decision cannot be appealed. Dominican authorities argue that such people will not be stateless, because they will qualify as Haitian citizens or will be given a path to Dominican citizenship. The Haitian constitution grants citizenship to children born of a Haitian parent, but does not address second and third generations descended from Haitian citizens. There are thousands more who will not be on Dominican registries because for decades, Dominican officials have denied birth certificates and other documents to many Dominican-born people of, or perceived to be of, Haitian descent. The ruling has heightened tensions with Haiti. With the possibility that the Dominican Republic could render thousands of second and third generation Dominicans of Haitian descent stateless and deport them to Haiti, the potential impact on Haiti could be enormous. Haiti has limited resources to deal effectively with an influx of that size of possible deportees who were not born in

The U.S. Department of Labor issued a report in September 2013 citing evidence of violations of labor law in the Dominican sugar sector such as payments below minimum wage, 12-hour work days and 7-day work weeks, lack of potable water, absence of safety equipment, child labor, and forced labor.

The Dominican government says it is trying to normalize a complicated immigration system. But U.N. and Organization of American States (OAS) agencies, foreign leaders, and human rights

groups have challenged the decision’s legitimacy, concerned that it violates international human rights obligations to which the Dominican Republic is party. The Inter-American Commission on

Human Rights (IACHR) concluded that the Constitutional Court’s ruling “implies an arbitrary deprivation of nationality” and “has a discriminatory effect, given that it primarily impacts Dominicans of Haitian descent.” The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) “condemn[ed] the abhorrent and discriminatory ruling,” and said it was “especially repugnant that the ruling ignores the 2005 judgment made by the Inter-American Court on Human Rights that the Dominican Republic adapt its immigration laws and practices in accordance with the provision of the American Convention on Human Rights.” CARICOM then suspended the Dominican Republic’s request for membership.

In May 2014, the Dominican Congress passed a bill proposed by President Medina setting up a system to grant citizenship to Dominican-born children of immigrants. The law created different categories, depending on whether people have documents proving they were born in the country. According to the Dominican government, those with birth certificates that are “irregular” because of their parents’ lack of immigration status will have their certificates legalized and will be confirmed as Dominican citizens. People without documents had 90 days to prove they were born in the Dominican Republic and register with the government; after two years of residency they could then apply for citizenship.109 Critics say the law continues to discriminate against people without documents.

On November 14, 2014, the Dominican Republic withdrew its membership in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The Inter-American Court found that the Dominican Republic

discriminates against Dominicans of Haitian descent and gave the government six months to invalidate the ruling of the Constitutional Court. The Dominican government charged that the

findings were “unacceptable” and “biased.” The Dominican Republic ended its “immigrant regularization” process on June 17, 2015, raising concerns that it may deport tens of thousands of people to Haiti. Most of those, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), are Dominican-born people of Haitian descent. The UNHCR appealed to the Dominican Republic government to ensure that “people who were arbitrarily deprived of their nationality as a result of [the] 2013 ruling … will not be deported.”112 The UNHCR expressed concern about the possible expulsion of people who are not considered Haitian citizens, which could create a new refugee situation. The UNHCR offered to work with the Dominican authorities to find an “adequate solution for this population and to ensure the protection of their human rights.”

Duvalier died at age 63 in Haiti on October 4, 2014. After he had unexpectedly returned from exile in 2011, private citizens filed charges of human rights violations against him for abuses they

allege they suffered under his 15-year regime. In 2012 a judge ruled that Duvalier could be tried for corruption, but that a statute of limitations would prevent him from being tried for any murder

claims. Upon appeal, however, a three-judge panel reversed that decision in February 2013. The appellate court ruled that Duvalier could be charged with crimes against humanity—such as

political torture, disappearances and murder—for which there is no statute of limitations under international law. Haitian human rights lawyer Pierre Esperance called the decision

“monumental.” Duvalier’s defense attorney Fritzo Canton said the judicial panel acted under the influence of “extreme leftist human rights organizations.”

Duvalier repeatedly failed to appear in court, then, under threat of arrest from the judge, appeared in court on February 28, 2013, much to the astonishment of many observers. When asked about murders, political imprisonment, summary execution, and forced exile under his government, the former dictator replied that “Murders exist in all countries; I did not intervene in the activities of the police.” Initially, Duvalier was not allowed to leave Haiti, but in December 2012 the Martelly government re-issued his diplomatic passport. He remained in the country, and was

President Martelly’s guest at official government ceremonies.

Former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide is also facing charges since his return in March 2011. A small group of people has filed a complaint against Aristide, alleging they were physically abused and used to raise money when they were children in the care of Aristide’s Fanmi se Lavi organization, created in the late 1980s to house and educate homeless children. A prosecutor

questioned Aristide in January 2013. Now a court must decide whether to dismiss the case or refer it to a judge to decide whether to file formal charges.

In May 2013 Aristide testified before a judge regarding an investigation into the murder of prominent Haitian journalist Jean Dominique in 2000. Thousands of supporters followed his

motorcade through the capital. Earlier in the year, former President Rene Préval, who was in office at the time of the murder, also testified in the case. Both men were once friends of

Dominique. At the time of his death Dominique was seen as a possible presidential candidate; Aristide was already preparing to run for a second term. Several people allegedly involved in the

assassination and witnesses have been killed or disappeared over the years. Dominique’s widow, Michele Montas, is a former journalist and U.N. spokeswoman. She says, “The

investigation has led to people close to the high levels of the Lavalas Family party that Aristide headed…. I am sure he knows who did it.” In January 2014 a Haitian appellate judge

recommended that nine people be charged for their alleged roles in Dominique’s murder. The investigative report alleged that a former Lavalas senator was the mastermind behind the crime

and that several others involved belonged to Aristide’s Lavalas Family party as well.122 It is now up to the Court of Appeals to accept or reject the judge’s report.

The government has an ongoing investigation into corruption, money laundering, and drug trafficking charges against Aristide. A judge issued an arrest warrant for Aristide in August 2014,

after which protesters blocked access to Aristide’s home. The same judges placed Aristide under house arrest on September 9, 2014. Some in the opposition claim the judge is close to President Martelly. According to IHS Global Insight, Aristide’s house arrest “is likely to strengthen opposition claims of persecution … [and] reduces the likelihood of a compromise agreement thatwould allow a second candidate registration process and the participation of opposition parties” in the overdue elections.

As a candidate, Martelly called for clemency for the former leaders, saying that, “If I come to power, I would like all the former presidents to become my advisors in order to profit from their experience.” He also said he was “ready” to work with officials who had served under the Duvalier regimes, and adult children of Duvalierists hold high positions in his government. Since becoming president, Martelly repeated the possibility that he would pardon Duvalier, citing a need for national reconciliation.127 He retracted at least one of those statements, and Prime Minister Lamothe stated that the Haitian state was not pursuing a pardon for Duvalier.

When MINUSTAH arrived in Haiti in 2004, there were about 5,000 officers in the HNP. About 1,000 new officers have been graduated from the police academy in recent years. The HNP now

has about 11,900 officers, including 1,022 women. MINUSTAH’s goal was to have at least 15,000 police officers trained by 2016.

In 2006 Congress passed the HOPE Act, or the Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through Partnership Encouragement Act (P.L. 109-432, Title V), providing trade preferences for U.S. imports of Haitian apparel. The act allows duty-free entry to specified apparel articles 50% of which were made and/or assembled in Haiti, the United States, or a country that is either a beneficiary of a U.S. trade preference program, or party to a U.S. free trade agreement (for the first three years; the percentage became higher after that). The act requires ongoing Haitian compliance with certain conditions, including making progress toward establishing a market based economy, the rule of law, elimination of trade barriers, economic policies to reduce poverty, a system to combat corruption, and protection of internationally recognized worker rights. It also stipulates that Haiti not engage in activities that undermine U.S. national security or foreign policy interests, or in gross violations of human rights. Those trade preferences were expanded in 2008 with passage of the second HOPE Act as part of the 2008 farm bill (Title XV, P.L. 110-246), in response to a food crisis and then-President Préval’s calls for increased U.S. investment in Haiti. HOPE II, as it is commonly referred to, extended tariff preferences through 2018, simplified the act’s rules, extended the types of fabric eligible for duty-free status, and permitted qualifying apparel to be shipped from the Dominican Republic as well as from Haiti. The act mandated creation of a program to monitor labor conditions in the apparel sector, and of a Labor Ombudsman to ensure the sector complies with internationally recognized worker rights.

Congress again amended the HOPE Act after the 2010 earthquake. Through the HELP, or Haiti Economic Lift Program Act (P.L. 111-171), Congress made the HOPE trade preferences more flexible and expansive, and extended them through September 2020. Supporters of these trade preferences maintain that they will encourage foreign investment and create jobs. Others argue that while the textile manufacturing sector may create jobs, some of the new industrial parks are being built on arable land and putting more farmers out of jobs, and that the manufacturing sector is being supported at the expense of the agricultural sector.

Legislation in the 114th Congress

P.L. 113-76/H.R. 3547. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014, prohibits assistance to the central government of Haiti until the Secretary of State certifies that Haiti has held free and fair parliamentary elections, is respecting judicial independence, and is taking effective steps to combat corruption and improve governance. The bill also prohibits the obligation or expenditure

of funds for Haiti except as provided through the regular notification procedures of the Committees on Appropriations, but allows Haiti to purchase defense articles and services under

the Arms Export Control Act for its Coast Guard. Signed into law January 17, 2014.

P.L. 113-162/H.R. 1749/S. 1104. The Assessing Progress in Haiti Act would measure the progress of recovery and development efforts in Haiti following the earthquake of January 12, 2010. It directs the Secretary of State to coordinate and transmit to Congress a three-year strategy for Haiti that identifies constraints to economic growth and to consolidation of democratic

government institutions; includes an action plan that outlines policy tools, technical assistance, and resources for addressing the highest priority constraints; and identifies specific steps and

benchmarks for providing direct assistance to the Haitian government. The act also requires the Secretary of State to report to Congress annually through December 31, 2017, on the status of

specific aspects of post-earthquake recovery and development efforts in Haiti. Signed into lawAugust 8, 2014.

P.L. 113-235/H.R. 83. The FY2015 Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act conditions aid to Haiti. It prohibits assistance to the central government of Haiti until the

Secretary of State certifies that Haiti “is taking steps” to hold free and fair parliamentary elections, respecting judicial independence, selecting judges in a transparent manner, combating

corruption, and improving governance and financial transparency.

H.R. 52. The Save America Comprehensive Immigration Act of 2015 would authorize adjustments of status for certain nationals or citizens of Haiti and would amend the Haitian

Refugee Immigration Fairness Act of 1998 to (1) waive document fraud as a ground of inadmissibility and (2) address determinations with respect to children. Introduced January 6,

2015, referred to the House Judiciary Committee, Committees on Homeland Security and Oversight and Government Reform January 23, 2015.

H.R. 1295. The Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015 would extend preferential duty treatment program for Haiti. Introduced March 4, 2015; House passed on April 15; Senate passed

amended version May 14; resolving differences as of June 11, 2015.

H.R. 1891. AGOA Extension and Enhancement Act of 2015 would extend the African Growth and Opportunity Act, the Generalized System of Preferences, and the preferential duty treatment

program for Haiti, and for other purposes. Introduced April 17, 2015, referred to the House Committee on Ways and Means. Referred to the Union Calendar, Calendar No. 70, May 1, 2015.

H.Res. 25. Would recognize the anniversary of the tragic earthquake in Haiti on January 12, 2010, honoring those who lost their lives, and expressing continued solidarity with the Haitian

people. Introduced January 9, 2015, referred to the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere on February 11, 2015.

S. 503. Haitian Partnership Renewal Act would amend the Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act to extend (1) the 60% applicable percentage requirement for duty-free entry apparel articles assembled in Haiti and import from Haiti or the Dominican Republic to the United States, and (2) duty-free entry for such articles through December 19, 2030. Introduced, referred to the Senate Finance Committee, read twice, and referred to the Committee on Finance on February 12, 2015. S. 1009. AGOA Extension and Enhancement Act of 2015 would extend the African Growth and Opportunity Act, the Generalized System of Preferences, the preferential duty treatment program for Haiti, and for other purposes. Introduced, referred to the Senate Finance Committee, read twice and referred to the Committee on Finance on April 20, 2015.

S. 1267. The Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015 would amend the Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act to extend through December 19, 2025, the duty-free entry of apparel

articles, including woven articles and certain knit articles, assembled in Haiti and imported from Haiti or other Dominican Republic to the United States; the special duty-free rules for Haiti shall now extend through September 30, 2025. Introduced May 11, 2015, referred to Senate Finance Committee. By Senator Hatch from Committee on Finance filed written report, S.Rept. 114-43, on May 12, 2015.