Education as a Fundamental Human Right

First, in order for a country to develop, it must have the adequate human capital to do so. Second, that human capital is obtained through education. Third, that education is a pivotal part of human development, and can positively influence standards of living, health, and governance.

Beginning in 1948, the international community recognized education as a fundamental human right, through Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948). Articles 13 and 14 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights further stipulate that ―primary education shall be free and compulsory to all, secondary and higher education shall be equally accessible to all, and the development of a system of schools at all levels shall be actively pursued,‖ (United Nations, 1948). These international benchmarks on education are based on the premise that education has a strong impact on a country‘s development.

Investment in universal education at all levels (primary, secondary, and higher) has been proven to have positive impacts on individuals, their community, and nations (Colclough, 1982); (Barro & Sala-i-Martin, 2003); (Barro & Lee, 2001); (Hanushek & Kimco, 2000); (Hanushek, 2003). This is because education serves as an ―equalizer‖ which helps shrink discriminatory socioeconomic and gender gaps within society (The World Bank, n.d.). Providing men and women, both rich and poor, an equal opportunity to gain foundational knowledge and expertise training in a particular field can significantly reduce poverty and inequality (The World Bank, n.d.). A more highly trained workforce increases national productivity, which leads to higher income and strengthens the economic health of a nation. This is a powerful contributor to development by allowing the country to become more competitive within the global market (The World Bank, n.d.).

Education not only leads to economic development but also health and human development. Health, as defined by the Education Development Centre, is not simply the absence of illness but the presence of physical, mental, and social welfare (The World Bank, n.d.). If people are healthy, they can take full advantage of every opportunity to learn, work, and enjoy their lives. Educated individuals are more likely to be knowledgeable on a variety of healthcare topics, such as hygiene, nutrition, and reproductive health, and can thus employ the proper tools to lead healthy lifestyles. Furthermore, because schools provide a space to learn positive social skills such as collaboration and conflict resolution, education has been linked with democratization, peace, and security (The World Bank, n.d.).

As detailed below, The World Bank further details the benefits of education on the individual and society, as follows (The World Bank, n.d.).

Benefits To The Individual

Education can have a profound impact on an individual‘s health and nutrition as well as productivity and earnings. The more educated a person is the more likely they receive information on proper hygiene, healthy dieting, and ways to prevent communicable diseases; all of which can lead to increased life expectancy. In addition, research has established that every year of schooling increases individual wages for both men and women by a worldwide average of 10 percent. In poor countries, the gains are even greater. Education can thus be a great ―leveler,‖ reducing social inequalities and enabling larger numbers of a population to share in the growth process. Even more, education is particularly powerful for girls, who gain critical knowledge about reproductive health, which may increase their child‘s mortality and welfare through better nutrition and higher immunization rates.

Benefits To Society

A more educated society is more economically competitive, environmentally conscious, and peaceful. An educated and skilled workforce is a pillar of the knowledge-based economy. This is important in a world where comparative advantages among nations come less from cheap labor or natural resources and increasingly from technical innovations and the competitive use of knowledge. Education can promote concern for the environment, thus enhancing natural resource management, national capacity for disaster prevention, and the adoption of new, environmentally friendly technologies. It can also significantly reduce crime as robust school environments can strengthen academic performance while mitigating absenteeism and dropout rates—precursors of delinquent and violent behavior. By promoting peace and stability education can also contribute to democratization. Peace education—spanning issues of human security, equity, justice, and intercultural understanding— is of paramount importance. Countries with higher rates of primary schooling and a smaller gap between rates of boys‘ and girls‘ schooling tend to enjoy greater democracy. Democratic political institutions (such as power-sharing and clean elections) are more likely to exist in countries with higher literacy rates and education levels.

Higher Education

Primary education, as opposed to higher education, tends to be the focus of education development initiatives, due to the perception that it has a greater direct impact on economic growth. However, a recent study suggests that higher education is both a result and a determinant of income, and can produce both public and private benefits (Bloom, Hartley, & Rosovsky, 2006). The study also suggests that higher education may create greater tax revenue, increase savings and investments, and may be the catalyst for a more entrepreneurial and civic society. Higher education can also improve technology and strengthen governance. Many observers attribute India‘s success in entering the world economic stage as stemming from its decades-long efforts to provide high-quality, technically oriented, tertiary education to a significant number of its citizens (Bloom, Canning, & Chan, 2006).

Education In Haiti

Prior to the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th and 19th centuries, education was the responsibility of parents and the church. At that time it was primarily available to the upper classes and thus served to further widen the socioeconomic gap between the working class and elite members of society (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011). With the onset of the French and American revolutions in the late 1700s, revolutionaries sought education to be recognized as a public good (Brockliss, 1987). As such, the state would assume an active role in the education sector making it accessible to all. The development of socialist theory in the nineteenth century further supported this view, as it emphasized that the state‘s primary responsibility was to ensure the economic and social well-being of the community through government intervention and regulation in all sectors. While pre-Enlightenment scholars believed education to be a privilege, the period after the revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries came to view education as a right (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011).

Education policy in Haiti, at that time, paralleled this thinking. The first Haitian Constitution of 1801 mirrored the pre-Enlightenment view of education that the private sector should ultimately be responsible for the education of its youth. The constitution stated that ―every person has the right to form private establishments for the education and instruction of youth‖ (Haiti Government, 1801). However, with the constitution revision of 1807, the practice of providing public education for all was established. Article 34 of the 1807 constitution establishes that ―A central school shall be established in each Division and proper schools shall be established in each District‖ (Haiti Government, 1807). However, despite the influence of the French on Haiti‘s state formation, it wasn‘t until more than 100 years after the French had established education as a human right that Haiti incorporated this principle into their constitution. In 1987, the GoH redrafted its 1987 Constitution of Haiti 1987-CONSTITUTION-OF-HAITI to include Article 22, which reads, ―The State recognizes the right of every citizen to decent housing, education, food and social security‖ (Haiti Government, 1987).

Despite the 1987-CONSTITUTION-OF-HAITI proclamation of education as a human right, many individuals still consider it a privilege to have the opportunity to attend school, where alternatively, in many other parts of the world, education is considered a human right. Families are often willing to sacrifice up to half their income, of approximately 400 USD annually, to send their children to school (McNulty, 2011). However, an inordinate number of children do not have the opportunity to enjoy the same privilege (Bruemmer, 2011). Of the approximately three to 3.5 million school-age children in Haiti, 800,000 do not have access to education (Bruemmer, 2011). In fact, Haitian public schools have the capacity to serve only one-quarter of the school-age population (The World Bank, 2006). Even before the earthquake, 25 percent of Haiti‘s school districts, mostly in rural areas, did not have a school. Due to these challenges, the average Haitian child receives only five years of education (Bruemmer, 2011).

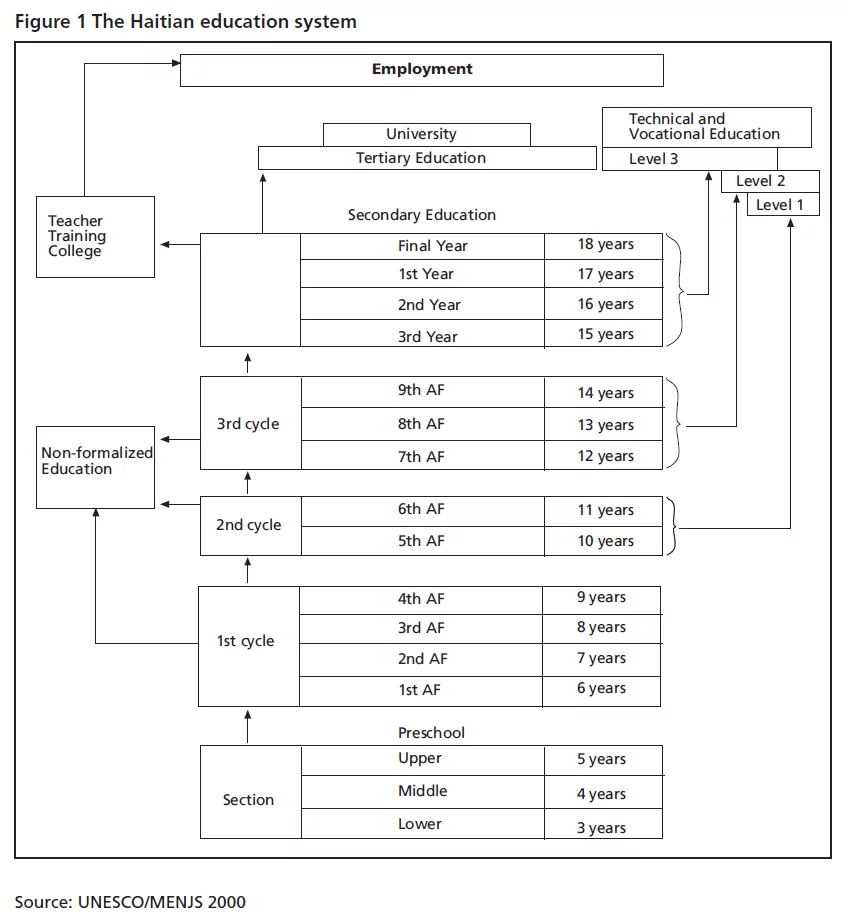

After completing nine years of primary school, the students can continue to secondary. Secondary education lasts for an additional four years, after which the students are qualified for university and professional training. The vocational and technical training falls into three categories. The most advanced are the Technical Education Institutes, which require completion of secondary education, hence 13 years of formal education. The second group consists of Vocational Education Schools. These are more practically oriented than the schools belonging to the first group and require the completion of the second cycle. The biggest category of vocational training is the Skill Training Centres which often do not require any prior education. The biggest group comprises the Skill Training Centres, and the vast majority of them are private, operating outside the control of the government.

Haitian Education System Charts

Weak Public Education Sector, Mixed Private Education Sector

To provide children with access to education is, by law, an obligation of the Haitian State. It is however a responsibility the weak state, marked by decades of dictatorships and economic mismanagement, has not proved capable, or willing, to take on. The government’s weak involvement in the education sector has created a huge market for private actors. Only 8 percent of Haitian primary schools are state-run (MENFP 2007). The remaining 92 percent of the schools are non-public; the vast majority of them do not receive any public subsidies. More than 80 percent of Haitian children currently enrolled in school are in private schools. Education in Haiti is a business, encompassing both serious and not-so-serious actors.

The high number of private education institutions, combined with the weak capacity of the MENFP, has left the Haitian government with little influence over the education sector. According to the Ministry’s own numbers, more than 75 percent of the private elementary schools do not have the mandatory license and are operating, unsanctioned, outside of government control. For these schools, the government has control of neither the quality of the education they offer nor the fees they charge.

Among the schools in the private sector, we find the very best and the very worst of what the Haitian education sector has to offer. At the top of the scale, we find a category of well-reputed, elite schools, what Haitians call “Lekol Tét Neg” or “big-shot schools”. Most of them are religiously founded and almost all of them are urban-based. They are well equipped, have the best teachers, and are the obvious choice for the privileged families who would never consider sending their children to a public school. However, private schools are also to be found at the very bottom of the scale. In the capital, Port-au-Prince, private primary schools are found on almost every street corner. Because of the density of them, people condescendingly call them “Lekol Borlette”, literally meaning “lottery schools”, named after the small lottery stands that are also found on every corner. Another explanation given for the name is that students in these schools are assumed to have the same probability of graduating as winning the lottery (Salmi 2000). These urban, private schools are usually short-lived and do not have the necessary competence and resources to provide quality teaching.

For some of the schools, the objective is clearly more directed towards making money than towards educating children, and often the classes are overfilled and the teachers unqualified. There are formal criteria set by the government to be followed when establishing a new school, hiring qualified teachers is one of them. However, as the majority of the private schools are operating unlicensed, getting around the formal criteria and starting up a new school is not too difficult if one has some resources and a few good contacts. In rural areas, community schools are often established by NGOs, local associations, or simply a local initiator with some basic schooling. Local churches are frequently used as facilities, or the teaching takes place in someone’s backyard or anba tonèl, under a makeshift roof without walls. Community schools make an important contribution in an area where the public sector is failing. However, they are struggling to get qualified teachers, learning materials, and suitable school buildings and are often incapable of offering the teaching of acceptable quality. Often they will only teach the first cycle, from first to fourth grade. Higher grades than that will in many cases exceed the teachers’ own level of education. The very low salaries make it impossible to attract qualified teachers to these rural positions.

The private schools are heterogeneous, not only in terms of quality but also in terms of ideology, organization, and motivations. While some private schools are established primarily for profit, many schools are also established for non-profit reasons by local initiators in communities where no public school is available, or the local public school does not have sufficient capacity. A number of schools are also run or supported by local or international NGOs, or religious communities. Some of these schools subsidize the students and have beneficial arrangements for marginalized families. However, in the context of such widespread poverty, non-profit actors are not able to fill all the gaps. One possible explanation for the low enrolment rate is that considerable variation in the quality of education is weakening the parents’ incentives to enroll their children if a high-quality school is out of reach because of economic reasons or due to geographical distance. If this is the case, simply increasing the number of schools will not necessarily lead to an improvement in the number of children enrolled in school if not steps are taken to also improve and level out the quality of education provided in the schools.

Private Education

There are approximately 16,000 to 17,000 primary schools in Haiti. Private sector schools account for roughly 80 percent of all schools (primary, secondary, higher education) (McNulty, 2011). Although it is considered to be the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, Haiti has the second-highest percentage of private school attendance in the world (Bruemmer, 2011). Article 32 of the 1987 Constitution Of Haiti stipulates that ―the State guarantees the right to education.‖ It goes on to say that primary schooling is compulsory under penalties to be prescribed by law. Classroom facilities and teaching materials shall be provided by the State to elementary school students free of charge (Haiti Government, 1987). As of the early 1900s, the government had only built 350 schools that primarily served the children of the political elite (Salmi, 1998). Eventually, religious, and then non-denominational, for-profit organizations built and staffed schools to fill the gap in services that the government was unable to provide. This has resulted in a system in which only 20 percent of students are served by the public school system and admission is highly competitive (Bruemmer, 2011). To date, the government‘s promises have not been realized and in fact, the reality is quite the opposite. Due to the severe lack of regulation and accountability mechanisms, private schools are able to charge tuition rates disproportionate to what the average Haitian household can feasibly bear. Annual tuition rates range from approximately 50 USD in rural areas to 250 USD in urban areas (Wolff, 2008). Given this history, the Haitian private education system has grown by default, rather than by the deliberate intention of the state (Salmi, 1998). However, if the GoH shut down the private education sector, its education system would collapse altogether.

Child Labour

Poverty and vulnerability are pushing far too many young children out of school and into the world of work. Some children remain in school but are disadvantaged doubling up studies with work. For households living in poverty, children may be pulled out of school and into work in the face of external shocks such as natural disasters, rising costs, or a parent’s sickness or unemployment. By leaving school to enter the labor market prematurely, children miss a chance to lift themselves, their families, and their communities out of a cycle of poverty. Sometimes children and restavek are exposed to the worst forms of labor that are damaging to their physical, mental, and emotional well-being.

Enrollment Rates

Haiti has one of the lowest enrollment rates in the world, with only 55 percent of children aged six to twelve enrolled in school, and less than one-third of those enrolled reaching fifth grade. According to ―Making a Quantitative Leap Forward,‖ the GoH‘s 2007 Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper, of the 123,000 students admitted to Haitian secondary schools in 2004, only 82,000, or 67 percent, were able to receive secondary schooling, and most of those who completed their secondary schooling were unable to eventually gain admission to a university (The World Bank, 2006). Low enrollment and high dropout rates are primarily due to economic hardship, high-grade repetition rates, and linguistic barriers (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). Language can become an obstacle to achieving education, primarily due to the fact that a majority of Haitian families speak Kreyòl in the home and the parents of many students are not French literate, yet lesson plans are taught in French. Additionally, many families are unable to pay the direct and indirect costs of education; therefore, many, especially those with multiple children, are forced to make difficult decisions in deciding which of their children will be provided an education. This ultimately leads to many children being withdrawn from school, which disproportionately affects girls (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). Some parents choose to rotate education opportunities among their children, allowing siblings to take turns attending school. This cycle of interrupted schooling leads to higher repetition rates, which in turn increases the cost of education for the family. Due in part to these factors, approximately 25 percent of those 15 to 29 years of age remain illiterate (Daumerie & Hardee, 2010).

Incentives And Disincentives To Education

In a western context with free education and nearly universal enrollment, whether a child should go to school or not is not a decision of the parents. Education is compulsory by law, and parents who prevent their children from attending school could face legal sanctions.

Incentives for basic-level education are as such, not decisive for whether or not a child will be given schooling. The value of education is taken for granted. Education is perceived as instrumental in terms of social mobility, as essential in terms of socializing children into good citizens, as well as having an intrinsic value for the child. Very few parents would question the importance of sending their children to school. When it concerns higher education, on the other hand, incentives become important.

Whether a young person chooses to proceed with higher education after finishing compulsory schooling may depend on whether he or she is accepted to the preferred school, the cost of the school, and the expected loss of income during the time of the study. He or she also needs to consider to what extent completing a higher education will lead to an advantage in the labor market, and perhaps most importantly – the alternative to continue with schooling. If the outlook of getting a better-paid job is not improved after additional years of education, the incentive to start working right away may be stronger than investing time and money in further schooling. Still many proceed with long educations that do not necessarily pay off in monetary terms in search of a job they find interesting, higher social status or because education is perceived as a value in itself. In a context where education is costly, access is limited, and enrollment in practice optional, the incentives for parents to enroll their children in school become important as early as at the primary level. Whether families with limited resources prioritize sending their children to school will be influenced by the perceived value of education, the quality of the educational system, and the alternatives available, for instance, the demand for child labor. If the children after finishing years of expensive schooling are still badly equipped for finding a skilled job or if the education system is structured in a way that makes it difficult to advance, the incentives for enrolling children in school are weakened. If the reasons for low enrollment are weak incentives for education, social protection initiatives (i.e., cash transfers and subsidized school fees) are not likely to have the desired effect. Instead, solutions should be explored in improved education and labor market policy.

Teacher Salaries

Within the existing structure, it is exceptionally difficult to attract and retain qualified teachers, especially in the public sector where teachers sometimes work for many months without receiving earned compensation. Low salaries, at approximately 60 USD per month, in both the public and private sector, resulting in high teacher turnover, in addition to many staff members not reporting to school on time and/or consistently (Lunde, 2008). The increased presence of international NGOs in Haiti since the earthquake has presented competition for quality personnel within Haiti‘s public education sector, as international organizations are typically able to offer higher wages. Low salaries also contribute to, and are partially responsible for, the brain drain effect in which large numbers of Haitians migrate in order to achieve a higher level of education and do not receive adequate incentives to return. It is estimated that 80 to 86 percent of Haitians with a secondary education leave the country (McNulty, 2011).

To be able to make a living, many of the rural school teachers need to supplement their salaries with agricultural activities. This means that the time they have access for teaching is reduced, in particular during the sowing and harvesting season. In Maissade it was also a concern that teachers cross the border to the Dominican Republic to work on the sugarcane plantations during the harvesting seasons. This may leave the children without teachers for weeks and months at a time. In order to pay the teachers, the schools are dependent upon collecting school fees from the students’ parents. As a significant number of the children who gain admission at the beginning of the school year drop out during the year, the total amount of income to the school is steadily reduced while their expenses remain the same. The result often delays in the payment of the teachers’ salaries. Teachers say that when this happens, they have to stay away for a while to put pressure on the directors to provide their pay. In the meantime, the children are missing out on their teaching and the preparations for their exams.

Lack Of Qualified Teachers

The lack of qualified teachers is one of the main problems in the Haitian education sector. The education sector suffered a serious blow during the time of the Duvalier regimes when large parts of the educated elite escaped to the US and Canada. Two decades later, Haiti is still suffering from the consequences of this void of professional capacity. There are few qualified instructors available to teach the next generation of teachers and other professionals. Among the few who do complete a higher education, many intend to leave Haiti and find a more prosperous future in the US, Canada or Europe. The ‘brain drain’ from Haiti is one of the most serious obstacles to reform and improvement within the education sector. According to the World Bank, a staggering eight out of ten Haitians with college degrees live outside of Haiti (Schiff & Caglar 2005). The fact that human resources in the country are so weak makes it very challenging to rebuild and improve the education system. In order to rebuild the education sector, as well as to strengthen the national capacity for development in general, it is essential to enact the constitutional changes necessary to allow double citizenship for Haitians settled abroad and encourage the return of the Diaspora. When UNESCO conducted an evaluation of the teachers’ competence in 1997, 25 percent or almost 11,500 teachers had not completed a primary education, a level equal to 9th grade. The majority of unqualified teachers were to be found in private schools. While 48 percent of the public schools teachers were qualified at the time of the survey, only 8 percent of the teachers in the private schools were qualified. Knowing that the number of unlicensed private schools has increased during the eleven years that has passed since this survey was conducted, it is more likely that the number of unqualified teachers in Haitian schools has increased rather than decreased. Although international donors like the World Bank have committed to increase the capacity of the teaching colleges, it will still take a number of years to fill the gap between the supply and demand of qualified teachers. A national test of the teachers’ knowledge in the subjects they are teaching was recently conducted by IHFOSED (Institut Haïtien de Formation en Sciences de l’Éducation). The preliminary results are depressing, revealing that large parts of the profession are not sufficiently trained to be able to teach the curriculum to the children. Often the teachers themselves have only completed a few grades more than the classes they are teaching, and without appropriate teaching material, they are ill equipped for providing the students the necessary teaching to obtain a satisfying level of knowledge and prepare them for their final exams.

Teachers’ salaries are low, making the profession unattractive to educated professionals. Teachers in public primary schools earn around 4000 HTG ($100 USD) per month. The salary is regulated according to a national wage system and adjusted depending on experience. The salaries for teachers in the private sector vary according to the quality of the school, but in the rural areas it is normally considerably lower than in the public schools. Private rural teachers on average make around 1500 HTG ($38 USD) per month. If the quality of education is weakening parents’ incentive to send their children to school, resources need to be directed towards teachers’ training. However, educating more teachers will not be sufficient if low wages in the education sector make alternative livelihoods more attractive, hence preventing teachers from working with education. In particular it is challenging to make teachers stay in the rural areas. In the experience of NGOs who provide teachers’ training, teachers who receive training find themselves qualified for better paid jobs in the cities and may chose to relocate, leaving the area even more deprived of teaching resources than before.

The education level achieved by most school teachers in Haiti is extremely low. On average, most private school teachers have completed nine years of schooling. In fact, only 20 percent of teachers in private schools are graduates of teacher training colleges (Salmi, 1998). The lack of professionally trained teachers contributes to the low quality of many Haitian schools. This is, again, due in part to poor wages and the migration of trained teachers abroad. The lack of teacher training is especially apparent in disciplines such as chemistry and physics, where teachers may be unable to conduct basic laboratory experiments (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010).

Lack Of Physical Access To Education

Lack of physical availability of schools is a problem in some of the more remote rural areas. In some areas, one is unable to find any schools within reasonable reach. More often there is a lack of access to affordable schools. The density of schools in rural areas is much lower than in urban areas. In particular, there is a lack of public schools, which is the only type of schooling many of the rural households can afford. Most Haitian households have access to a primary school within five kilometers. For 92 percent of the population, it takes half an hour or less to walk to the nearest primary school (EMMUS III 2000). What this number conceals is that the low capacity in the local schools may make it necessary for children to enroll in schools further away from their homes. The nearest school may also be out of reach due to economic costs. Less than 10 percent of the schools are public and, as is the case with all public infrastructures in Haiti, the public schools are concentrated in the urban areas or in the regional centers. The further away from the center one lives in, the less the chance of finding a public school within your area. Private schools often cost more per month than the public does per year. For many parents, the only way to get their children into school is to try to get them into one of the public schools, even if that means that their children will have to walk for hours every day.

In Jacmel, a public primary school in Meyer, an area outside the town center is the only public primary school in the Meyer region. The students came from all across the region, many of them from areas far away, as far as Cap-Rouge. The walk from Cap-Rouge to Meyer takes approximately 2.5 hours each way. To be able to reach school in time for their morning classes, the children have to get up before dawn. Some of them, in particular girls, also have to help with domestic tasks before leaving their home in the morning. As a result, the children are tired and hungry when they reach school, making them unfocused and inattentive during classes. The teachers claim that the children are so tired from walking and getting up early that they fall asleep during the classes.

The story repeated itself in other public schools. According to the teachers, children as young as the first grade will walk for hours in order to get to school. The long-distance is the main reason why children drop out during the school year, not economic concerns. “Some of the parents will tell you that”, “but the real reason is that the children are just too tired.” In September, at the beginning of the school year, the public school in Meyer had 416 students. In early December this number drops to 370 students. In addition, many of the children had a low attendance rate. Since Meyer is a public school, the school fees are paid at the beginning of the year, instead of at monthly rates which is the practice in private schools. It is reasonable to expect the long distance to be an important reason for children to stop coming to school. When the walk exceeds several hours every day, it does become tiresome, especially for the youngest children. Some of the families try to solve the problem by sending their children to school only some days a week, but without sufficient attendance, the children risk failing their exams and find themselves in a situation where they have to repeat the class the following year.

The long-distance is also likely to be a contributing factor why many Haitian children are over-aged at the time of enrollment Parents do not want to send their six years old out on long daily walks, and instead delay their entry until they are older. The long-distance to school is a disincentive both for the parents to send their children and for the children to attend. The parents may be concerned about sending their youngest out early in the morning while it still is dark, in particular, they may feel uneasy about letting girls walk alone. Concerning older children, these are likely to have more responsibility within the household. The more time the children spend away from home for school, the less time they have available for performing domestic tasks, working on farmland, or helping out with the family business. If the family is dependent upon help from the children, the additional time spent on getting to and from school will strengthen the incentive to keep them at home. Long daily walks may also weaken the children’s motivation for going to school.

Access To The Complete Cycle Of Education

While most Haitian households do have a primary school teaching, the first, and often also the second cycle within physical, although not necessarily economic reach, the schools teaching higher grades are more strongly concentrated in the central areas. According to the Demographic Health Survey from 2000, only 28 percent of the rural households have schools that teach the third cycle within five kilometers, while for 26 percent the nearest school that teaches the third cycle is more than 15 kilometers away (EMMUS III 2000). The lack of access to schools teaching higher grades, in addition to a steep increase in costs when students move on from the second to the third cycle, has led to a huge gap in third cycle enrollment in urban and rural areas. While more than 40 percent of the children in and around Port-au-Prince continue to 7th grade, less than 10 percent of the children in the rural areas do so. For the other urban areas, the enrollment rate is around 30 percent (IHSI/Fafo 2003). In order to continue education beyond the 4th or 6th grade, the rural children will often have to travel long distances daily or go and stay with urban households in Port-au-Prince or other central areas. These boarding arrangements take many different shapes. Often the host families will be relatives or close friends of the family, but boarding is also arranged with strangers through intermediaries. In its strictest sense, parents pay the child’s school expenses, in addition to board and upkeep to the household where the child is staying. In other cases, the parents will donate gifts and shares of the agricultural harvest to the host family, while the students may be contributing to the household with domestic work. This should not be confused with restavek-arrangements where children from poor families are placed in (at times marginally) more prosperous households, with hopes that they will be given an education in exchange for domestic work. These children are usually denied schooling and simply end up as unpaid domestic workers (Sommerfelt 2002).

In general, in all places outside the capital, people portray a negative picture of Port-au-Prince as an unsafe place they would not go if they did not absolutely need to. Rather than sending their children to Port-au-Prince in order to pursue their education, parents want the possibility of letting the children complete their studies in their area of origin.

Expectations Of Education

The Haitian education system is designed so that students need to complete both primary and secondary levels, altogether 13 years of schooling, before they can apply for a technical school or university. For most Haitian children this is far beyond their reach. Still, Haitian parents have very high expectations about how far their children will continue their education. When discussing at what level education starts to pay off and how long the children need to stay in school to be able to find a qualified job afterward, most respondents replied that they would need a university degree. “To complete primary school is of no use”, one respondent argued, “you can have a conversation, but you can’t get a job”. Literacy is recognized as an important and highly valued skill, but being able to read and write was not seen as sufficient for achieving an advantage in the labor market. For the vast majority of the people, it would demand a dramatic improvement in their living conditions to be able to support their children all the way through university. Nevertheless, the people in the rural areas both in the south and in the central areas assigned a high priority to give their children the opportunity for an education. As the agricultural output is decreasing with deteriorating soil quality, the need for parents to make their children capable of finding a job outside the agricultural sector becomes more pressing. There are few jobs available on the countryside and it is hard for rural migrants to succeed in the cities. The reason why Haitian parents have such high expectations regarding their children’s education needs to be seen in relation to the lack of an intermediary level of education discussed previously. Another reason for the lack of value assigned to lower levels of education is the importance of personal connections in getting a job. “It is an illusion that education leads to employment”, one of our respondents uttered in resignation. “It is just a trap. Something they want you to believe. The only thing that leads to employment is knowing the right people”. It is a discouraging fact that having the right connections is an important asset in gaining access to work, but also in many cases to education.

The general impression is that people place a high value on education and are willing to go far in order to give their children the opportunity of schooling. From townspeople in Port-au-Prince and NGO-workers, it is sometimes argued that people in the countryside do not see education as important and place too low priority on sending their children to school. This is seen as a contributing factor to the large discrepancy between enrollment in rural and urban areas. The underlying assumption is that rural people are ignorant and unable or unwilling to make the right decisions for their children. If this was to be the fact, judicial interventions sanctioning parents against not sending their children to school could be an appropriate response. It is an uncomfortable truth that not all parents always act in the best interest of their children. This can have a number of idiosyncratic causes like substance abuse, mental illness or simply a lack of altruistic disposition towards their own children for unknown reasons. Child abuse is taking place in all societies at all times. Parents cannot always be trusted to protect the interests of their children, which is why children are entitled to legal protection both through national laws and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Nevertheless, in a Haitian context where the education sector is unable to absorb the number of children of compulsory school age, the quality of education often is not up to standard and widespread poverty is making it impossible for many to pay the school expenses of their children, sanctioning parents is not the way to go. First of all, education needs to be made physically and economically accessible. Secondly, the education provided needs to be made relevant. It is important to note that marginalized families’ actions are motivated out of survival of the household, sometimes at the expense of the well-being of the individual member. Will investments in education lead to jobs for household members and increased income to the household? If the answer to these questions is no, it may be a rational decision by the poorest households not to spend money on sending children to school, but instead prioritize the limited resources towards food, fertilizers, and medicines to ensure household survival. Marginalized households need to engage in a number of strategies to ensure the survival of the household, sometimes at the expense of opportunities for the individual members.

Classrooms

Classroom sizes often surge to more than 70 children per, with one teacher presiding (Kenny, 2011). Naturally, classrooms populated with such high numbers of students are too large for one teacher to manage. This creates an environment in which children are unable to ask questions, receive thoughtful feedback, and do not receive individualized attention. Classrooms are typically ill-equipped, lacking textbooks, desks, chairs, and basic teaching materials, such as chalk. There is a severe lack of school spaces, especially in areas hardest hit by the earthquake, to accommodate the numbers of school-age children, in addition to a lack of technology in nearly all schools such as computers and Internet access, which further curtails learning (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). Schools vary in appearance from plain cinder-block structures with wooden benches and outdoor latrines to those with brightly colored walls and modern amenities.

Vulnerabilities And Constraints

Poor people normally have low resilience to risks threatening their well-being. They often lack economic buffers like savings or access to credit, as well as access to formal risk management arrangements like insurance or welfare benefits (Holzmann and Jørgensen 2000). A failed harvest, for instance, can be disastrous to a farmer without savings or access to credit. Some of the risks that make households vulnerable are idiosyncratic, like illness or death in the family, crime, or unemployment. Other risks are threatening on a community or macro level, like natural disasters, epidemics, riots, or war. Whether the risks are unforeseen or predicted might be of less relevance if a household lacks resources to prevent or avoid the events. The household remains vulnerable but may engage in different mitigation strategies to decrease the potential impact of future risk. Examples of mitigation strategies may be to diversify agricultural production, vary different sources of income, participate in informal saving arrangements or extend social networks, for instance through child placement or marriage.

To not enroll all children in school, but instead have some work at home and let some live with other households may be a part of such a mitigation strategy. When harmful events occur, households engage in coping strategies to relive the impact of the risk. Examples of coping strategies may be to sell assets, borrow money, migrate, sell labor, reduce consumption by, for instance, reducing food intake for some or all household members, or take children out of school. To understand the behavior and organization of poor households, it is important to identify what kind of risks they are vulnerable to and what strategies they engage in to ensure the survival of the household. If non-enrollment of children is a result of household poverty or a part of a risk management strategy for vulnerable households, this calls for social policy interventions that can increase the households’ resilience to risks, for instance, access to credit or insurance arrangements.

It is important to recognize that the options available to the poorest households are severely limited by their lack of resources. For the most marginalized households, the money needed to send their children to school may exceed the total income of the household. Not enrolling children can as such not be seen as a part of a household strategy. Instead, the lack of economic resources is a binding constraint that does not allow enrollment of all children as an option to the household. In these cases, cash transfers to the households may be a way of ensuring education for the children, under the assumption that households place a high value on the education of their children. The high rates of dropout and failures can be interpreted in this direction. Enrolling children in school is a risky investment if you know chances are they will not be able to complete the full year or be allowed to proceed to the next grade. Alternatively, it can be interpreted in the opposite direction that education is not given a high value and that taking children out of school in difficult periods as such is not seen as entailing a high cost. How households prioritize taking children out of school in comparison with alternative coping strategies gives an indication of how important education is perceived to be.

School Expenditure As a Constraint To Education

Being one of the 20 poorest countries in the world, Haiti is the only country in which more than half of the students are enrolled in private schools (The World Bank 2006). The consequence of the privatization of the education system is that private households are carrying the economic burden of both the real cost of education and the private actors’ profit. The fact that more than three-quarters of the population live in poverty (defined as less than $2 USD per day) and more than half of the population live in extreme poverty (defined as less than $1 USD per day) makes it evident that the cost of schooling is a major obstacle to universal education for Haitian children (Egset & Sletten 2004). The percent of people living in poverty is twice as high in the rural areas as in the metropolitan area (82 percent vs 41 percent) and the share of people living in extreme poverty is three times higher (59 percent vs 20 percent). The population in urban areas other than the metropolitan Port-au-Prince area finds themselves between these two extremes. The difference in urban and rural income is also reflected in the enrolment of children in primary education. According to the Haiti Living Condition Survey, half of the children of compulsory school age in rural areas are not in school, while the corresponding share for the urban areas is one out of four (IHSI/Fafo 2003). In public schools, the school fees are paid at the beginning of the year, as opposed to private schools where the students pay every month. The school fees for public primary schools are set by the government to a total of 100 HTG per year, a little more than $2.5 USD. For private primary schools, the fees vary significantly, from a few hundred gourdes per year for community schools to several thousand per month for the more well-reputed urban schools. The household also needs to cover the costs of uniforms, shoes, books, and other learning materials. The expenditures for textbooks alone can easily exceed 1000 – 2000 HTG per grade. For the poorest half of the population, this equals around 10 percent of their income per child per year in textbooks only. Despite the school fees for public primary schools being regulated by the state, there are cases where the fees the parents ended up paying were substantially higher. For instance, in one of the rural communities in Département du Sud-Est, parents reported that the director at the local public primary school demanded 400 HTG per year in school fees. No attempt was made to justify to the parents why they were charged fees four times higher than what has been decided by the national government. Due to the lack of capacity in the public schools and since private schools are even more expensive, the parents feel that they have no other option than to comply and pay what is asked of them. The parents’ lack of alternatives makes them vulnerable to exploitation from opportunistic actors, both from the public and private sectors. Parents with children in private schools have the monthly obligation to pay their children’s

school fees. Many fail in doing so, with the result that their children are forced to drop out, and, if lucky, only get a chance to try again the following year. However, among children in public schools as well there is a high dropout rate during the year. The parents reported that it was the exam fees at the end of the year which caused them the most problems. If they are not able to raise the money necessary to pay for the exams at the end of the year, the children are not allowed to sit for their exams and the whole year is lost. This contributes to the high dropout rates, as early as the first years of primary school. Many children are been denied promotion from first to second, or second to third, grade because of their parents’ lack of ability to pay for their exams.

Accreditation And National Testing

As mentioned previously, there is very little regulation, oversight or monitoring of the education system in Haiti. Instructors do not require teaching degrees or certifications, there are no official/legal permits to be obtained, and there is no standard curriculum (McNulty, 2011). However, it should be noted that the Haitian public school curriculum has been adapted to that of France since 1958.

The GoH does not have official school accreditations. At the time of the earthquake, there were only ten ―accredited‖ schools in the country. These accreditations were achieved through three different external systems: the US Agency for International Development (USAID), The World Bank, and the IDB (McNulty, 2011). The primary tool by which the GoH monitors the standards of its public schools is through annual national exam testing. The Ministry of Education implements yearly national testing administered in all recognized public and private institutions completing sixth, ninth, eleventh, and twelfth grades. The tests are similar in content to those administered four decades ago in France and those currently offered in francophone African countries (Wolff, 2008).

Government Spending On Education

Although the education system in Haiti is largely inadequate, the government is not in a position to close deficient schools, as it is not equipped to take on the additional responsibility, nor does it have the resources or capacity to do so. Before the earthquake, the GoH was spending approximately 100 million USD per year on schools, approximately two percent of its GDP and approximately 41 USD per student. This is slightly less than half the regional average of budget allocation for public education (McNulty, 2011).

Additionally, the education system suffers from rural neglect. It is highly geographically centralized, with only 20 percent of education-related expenditures reaching rural areas, which account for 70 percent of Haiti‘s population (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). Of the total number of universities in Haiti, 87 percent were located within or in close proximity to Port-au-Prince before the earthquake (INURED, 2010). To further illustrate this point, in 2007, 23 communal sectors lacked a school, and 145 were without a public school, all located in rural areas (The World Bank, 2006).

Language Of Instruction

Kreyòl and French are the two official languages of Haiti and most, if not all, formal government and private sector communications are conducted in French. However, typically, the language of instruction in primary schools is in Kreyòl. It is unclear at what grade level instruction shifts to French. What is known is that the national examinations are administered in French, regardless of the fact that most Haitian families speak Kreyòl in their homes on a daily basis. There are great inconsistencies in the language of instruction by region, level, and subject matter (Wolff, 2008).

The Haitian Ministry Of National Education And Professional Training

The Haitian Ministry of National Education and Professional Training (MENFP) is charged with regulating the education system in Haiti. The ministry‘s mission is twofold: to provide education services to its citizens and to play a normative and regulatory role (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). However, MENFP does not have the capacity to meet its mandate of monitoring, evaluating, and reporting on the academic performance of schools primarily because it is overburdened and lacking adequate support (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). For example, there is one inspector responsible for providing accreditation, pedagogical supervision, and administrative support for every six thousand students (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). Organizationally, the governance and policy-making functions are not separated from management functions and currently, an independent policy-making body does not exist (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010).

Previous Education Reforms

The current education reform in Haiti is but one of many previous efforts to revitalize the education system. Three major recent reform efforts were The Bernard Reform of 1978, The National Plan for Education and Training (NPET) of 1997, and The Presidential Commission for Education in Haiti of 2008. The Bernard Reform was an attempt to modernize the Haitian education system. The Bernard Reform sought to align the educational structure with labor market demands by introducing vocational training programs designed as alternatives to traditional education. In addition, Kreyòl began to be utilized in classrooms as the language of instruction in the first four grades of primary school during this time period (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). The National Plan for Education and Training was a plan that introduced a shift away from the French education model (Luzincourt & Gulbrandson, 2010). One of the principal goals of this plan was to ensure that primary education would be made compulsory and free, neither of which have been realized to date.

More recently, The Presidential Commission for Education in Haiti, headed by Jacky Lumarque, rector of Université Quisqueya, set forth recommendations for the new national curriculum to outgoing Haitian President Préval and the Ministry of Education. Post-earthquake, Lumarque redrafted proposals for a National Education Pact. In doing so he consulted a wide cross-section of parents, teachers, students, and education NGOs on the issue. The primary goals are 100 percent enrollment of all school-age children, free education to all, including textbooks and materials, and a hot meal daily for each child. Lumarque stated that accelerated teacher training is essential for this work. The commission traveled throughout the country asking parents and community leaders what they desired most for their children. When the national curriculum plan is finalized, all public schools and those private schools that choose to participate in the education reform plan are expected to begin utilizing standardized teaching materials in addition to standardized methods to test students (McNulty, 2011).

In April 2011, Michel Martelly was declared President-elect of Haiti, succeeding outgoing two-term President Préval. On April 20, 2011, press conference with US Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, President-elect Martelly remarked on the priorities he had emphasized during his presidential campaign. He spoke briefly about his top three priorities, one of which is education (US Department of State, 2011). Five days later, Martelly asked Haitians living abroad to contribute to a new fund for education. He told reporters that his cabinet intends to create an education fund that will ensure free primary schooling for Haitian children,‖ (Fletcher, 2011).

Inter-American Development Bank

In May 2010, the GoH chose the IDB as its main partner in restructuring the education system and gave it the mandate to work with Haiti‘s Ministry of Education and the National Education Commission to help institute a major reform (Bruemmer, 2011). This is a five-year, 4.2 billion USD plan calling for private schools to become publicly funded, resulting in all children having equal access to free education. The plan proposes to have all children enrolled in free education up to sixth grade by 2015, and ninth grade by 2020 (Bruemmer, 2011). The IDB has committed 250 million USD of its own grant resources and has pledged to raise an additional 250 million USD from third-party donors. The IHRC, whose members include Co-Presidents Prime Minister of Haiti, Jean-Max Bellerive, and former US President William Clinton, approved the IDB proposal on August 17, 2010.

The first phase of the plan is to subsidize existing private schools. According to the plan, the government would pay the salaries of teachers and administrators participating in the new system (Bruemmer, 2011). In order to participate in this new system, schools will undergo a certification process to verify the number of students and staff at their school, after which they will receive funding to upgrade facilities and purchase education materials (Bruemmer, 2011). This is a first move towards establishing tracking mechanisms, which are currently non-existent. In order to remain certified, schools must continue to be compliant with increasingly demanding standards, including the adoption of a national curriculum, teacher training, and facility improvement programs. The plan will also finance the building of new schools and the use of school spaces to provide services such as nutrition and health care (Bruemmer, 2011).

To qualify, schools must be structurally sound, offer free tuition, and must adopt the new national curriculum, which will include annual student testing and two years of mandatory training for teachers (IDB, 2010). The goals are to eliminate low-quality, inefficient schools and consolidate many others over time. Currently, most private schools serve approximately 100 students; yet they have the capacity for up to 400 (McNulty, 2011). The intention is to eliminate waste and to increase the productivity and efficiency of the system.

Higher Education

All levels of the education system are highly geographically centralized, especially that of higher education. Before the earthquake, 139 of Haiti‘s 159 post-secondary learning institutions were located in Port-au-Prince (INURED, 2010). These included professional and vocational schools, technical schools and traditional universities. It should be noted, however, that the Ministry of Education is unable to provide an accurate accounting due to the lack of tracking mechanisms. Of these 159 institutions, 145 were private and of those, only 10 provide ―accredited‖ education. INURED reported in their March 2010 Post-Earthquake Assessment of Higher Education that of the remaining 135 institutions, 67 percent do not have permission to operate from the governmental Agency for Higher Education and Scientific Research (INURED, 2010). It is unclear why they are operating without permission or if permission was sought after. The University of Haiti is the largest institution of higher education in Haiti. In 2005, it served 15,000 students and employed 800 teachers, which equates to 38 percent of the total number of students enrolled in higher education in the country (Gosselin & Pierre, 2007). In 2007, MENFP reported the university population of Haiti to be approximately 40,000 students. Of these students, 28,000 attended public universities and 12,000 were enrolled in private institutions (Wolff, 2008).

Universities typically experience a shortage of adequately trained professors, libraries, textbooks, teaching materials, laboratories, and online resources. There is also a lack of emphasis on academic research (INURED, 2010). Additionally, there is an imbalance between student enrollment rates and the number of teachers hired. Between 1981 and 2005, student enrollments rose from 4,099 to 15,000 (MENJS, 2001). However, the number of professors staffed did not meet the increased demand. During the same time period, the number of teachers rose only from 559 to 700 (US Library of Congress, 1989).

Impact Of The Earthquake

The earthquake severely interrupted education for students nationwide. It is estimated that approximately 1.3 million children and youth under 18 were directly or indirectly affected. Of this population, 700,000 were primary-school-age children between six and 12 years old. However, it is unknown precisely how many casualties there were in total. What is clear is that the earthquake killed and injured thousands of students and hundreds of professors and school administrators (INURED, 2010). Most schools, even if minimally or not structurally affected, were closed for many months following and it was normative for individuals to refuse to enter standing buildings, out of fear. More than a year after the earthquake, many schools remained closed and, in many cases, tents and other semi-permanent structures have become temporary replacements for damaged or closed schools (INEE, 2004). By early 2011, more than one million people, approximately 380,000 of whom are children, remained in crowded internally displaced people camps (UNICEF, 2011).

The Haitian Ministry of Education estimates that the earthquake affected 4,992 (23 percent) of the nation‘s schools. Of these, 3,978 (80 percent) of the schools were either damaged or destroyed, affecting nearly 50 percent of Haiti‘s total school and university population, and 90 percent of students in Port-au-Prince (Haiti Special Envoy to the United Nations, 2008). Higher education institutions were hit especially hard, with 87 percent gravely damaged or completely demolished (INURED, 2010). In addition, the Ministry of Education building was completely destroyed (UNESCO, 2010). The cost of destruction and damage to establishments at all levels of the education system and to equipment is estimated at 478.9 million USD (Haiti Government, 2010). Another residual effect has been the number of children disabled by resulting injuries. Prior to the earthquake, approximately 200,000 children lived with disabilities in Haiti and as a result of the earthquake many more were injured and are experiencing long-term or permanent disabilities (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2010).