The death toll from a cholera outbreak in Haiti has leapt past 250.

More than 3,000 people are infected, said Gabriel Thimote, director general of Haiti’s health department.

Five cases of cholera were detected in the capital, Port-au-Prince, but UN officials said the patients had been quickly diagnosed and isolated.

Officials say the disease is a serious threat to the 1.3 million survivors of January’s earthquake who are living in tented camps surrounding the city.

“The worst case would be that we have hundreds of thousands of people getting sick at the same time,” said the president of the Haiti Medical Association, Claude Surena.

But Mr Thimote expressed optimism the outbreak could be contained.

“We have registered a diminishing in numbers of deaths and of hospitalised people in the most critical areas,” he said.

“The tendency is that it is stabilising, without being able to say that we have reached a peak.”

Quick killer

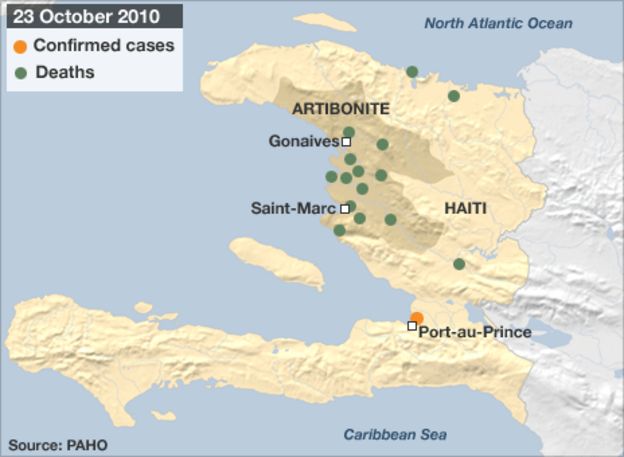

Health officials have been trying to contain the outbreak in areas north of Port-au-Prince.

The five victims isolated in Port-au-Prince had become infected in the Artibonite region – the main outbreak zone – and then travelled to the capital where they developed symptoms, the UN’s Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said.

“These cases thus do not represent a spread of the epidemic because this is not a new location of infection,” it said, adding that the development was nevertheless “worrying”.

Aid officials have described the prospect of a cholera outbreak in the city as “awful”.

Those in the camps are highly vulnerable to the intestinal infection, which is caused by bacteria transmitted through contaminated water or food.

Cholera causes diarrhoea and vomiting leading to severe dehydration, and can kill quickly if left untreated through rehydration and antibiotics.

The worst-hit areas of the outbreak were Saint-Marc, Grande Saline, L’Estere, Marchand Dessalines, Desdunes, Petite Riviere, Lachapelle, and St Michel de l’Attalaye, said the UN.

A number of cases have also been reported in the city of Gonaives, and towns closer to the capital, including Archaei, Limbe and Mirebalais.

‘Contaminated’ river

Many hospitals have been overwhelmed, with patients at the St Nicholas hospital in Saint-Marc being being left to lie outside in unhygienic conditions, hooked up to intravenous drips.

The aid agency Medicins Sans Frontieres has set up a cordon around the hospital to control exit and entry to try to contain the spread of the outbreak.

Dr John Fequiere told the BBC that his hospital in Marchand Dessalines was also struggling to cope, and that he had seen dozens die.

“We are trying to take care of people, but we are running out of medicine and need additional medical care. We are giving everything we have but we need more to keep taking care of people,” he said.

Some patients said they became ill after drinking water from a canal, but others said they were drinking only purified water.

The Artibonite river, which irrigates central Haiti, is thought to be contaminated.

Haitian Health Minister Alex Larsen has urged people to wash their hands with soap, not eat raw vegetables, boil all food and drinking water, and avoid bathing in and drinking from rivers.

This is the first time in a century that cholera has struck the nation, which has enough antibiotics to treat 100,000 cases of cholera and intravenous fluids to treat 30,000, according to the UN.

Haiti – the poorest country in the region – is still reeling from January’s devastating quake, which killed up to 300,000 people.

Seismic experts say that quake may have been caused by an unseen fault, and that pressure could be building for another tremor.

The journal Nature Geoscience has published two papers which both conclude the fault originally blamed for the quake was not the real source, and that it remains a threat.

“As the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault did not release any significant accumulated elastic strain, it remains a significant seismic threat for Haiti and for Port-au-Prince in particular,” concluded one report written by Eric Calais of Purdue University in Indiana.